by John Mundt

The Fly-Fishing merit badge: I must admit to a slight sense of apprehension when I first picked up the diminutive Merit Badge Series booklet, Fly-Fishing, one summer day while spending a week with my son Jack at our local Boy Scouts of America (BSA) camp. I’m a lifelong fly fisherman. Would this compact volume designed for instructing teenage boys reveal large voids in my general knowledge of the sport? Would I be able to meet the ten requirements without having to shuffle through its pages to learn the answers? I began to read:

Do the following:

- Explain to your counselor the most likely hazards you may encounter while participating in fly-fishing activities and what you should do to anticipate, help prevent, mitigate, and respond to these hazards. Name and explain five safety practices you should always follow while fly-fishing. Discuss the prevention of and treatment for health concerns that could occur while fly-fishing, including cuts and scratches, puncture wounds, insect bites, hypothermia, dehydration, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and sunburn.

- Explain how to remove a hook that has lodged in your arm.

- Demonstrate how to match a fly rod, line, and leader to achieve a balanced system. Discuss several types of fly lines, and explain how and when each would be used. Review with your counselor how to care for this equipment.

- Demonstrate how to tie proper knots to prepare a fly rod for fishing:

- Tie a backing to a fly reel spool using the arbor knot.

- Attach backing to fly line using the nail knot.

- Attach a leader to fly line using the needle knot, nail knot, or a loop-to-loop connection.

- Add a tippet to a leader using a loop-to-loop connection or blood knot.

- Tie a fly onto the terminal end of the leader using the improved clinch knot.

- Explain how and when each of the following types of flies is used: dry flies, wet flies, nymphs, streamers, bass bugs, poppers, and saltwater flies. Tell what each one imitates. Tie at least two types of the flies mentioned in this requirement.

- Demonstrate the ability to cast a fly 30 feet consistently and accurately using both overhead and roll cast techniques.

- Go to a suitable fishing location and make observations on what fish may be eating both above and beneath the water’s surface. Look for flying insects and some that may be on or beneath the water’s surface. Explain the importance of matching the hatch.

Do the following:

- Explain the importance of practicing Leave No Trace techniques. Discuss the positive effects of Leave No Trace on fishing resources.

- Discuss the meaning and importance of catch and release. Describe how to properly release a fish safely to the water.

- Obtain and review a copy of the regulations affecting game fishing where you live or where you plan to fish. Explain why they were adopted and what is accomplished by following them.

- Discuss what good outdoor sportsmanlike behavior is and how it relates to anglers. Tell how the Outdoor Code of the Boy Scouts of America relates to a fishing enthusiast, including the aspects of littering, trespassing, courteous behavior, and obeying fishing regulations.

- Catch at least one fish. If regulations and health concerns permit, clean and cook a fish you have caught. Otherwise, acquire a fish and cook it.1

With a slight sense of relief, I checked off the list without distress. My paranoia out of the way, I soon discovered that the merit badge booklet contained plenty of useful information. For example, it taught me how to tie the Duncan loop, a knot that I had never tried before. As a new adult advisor for older scouts teaching the course, my confidence was renewed.

Fly Fishing From the Start

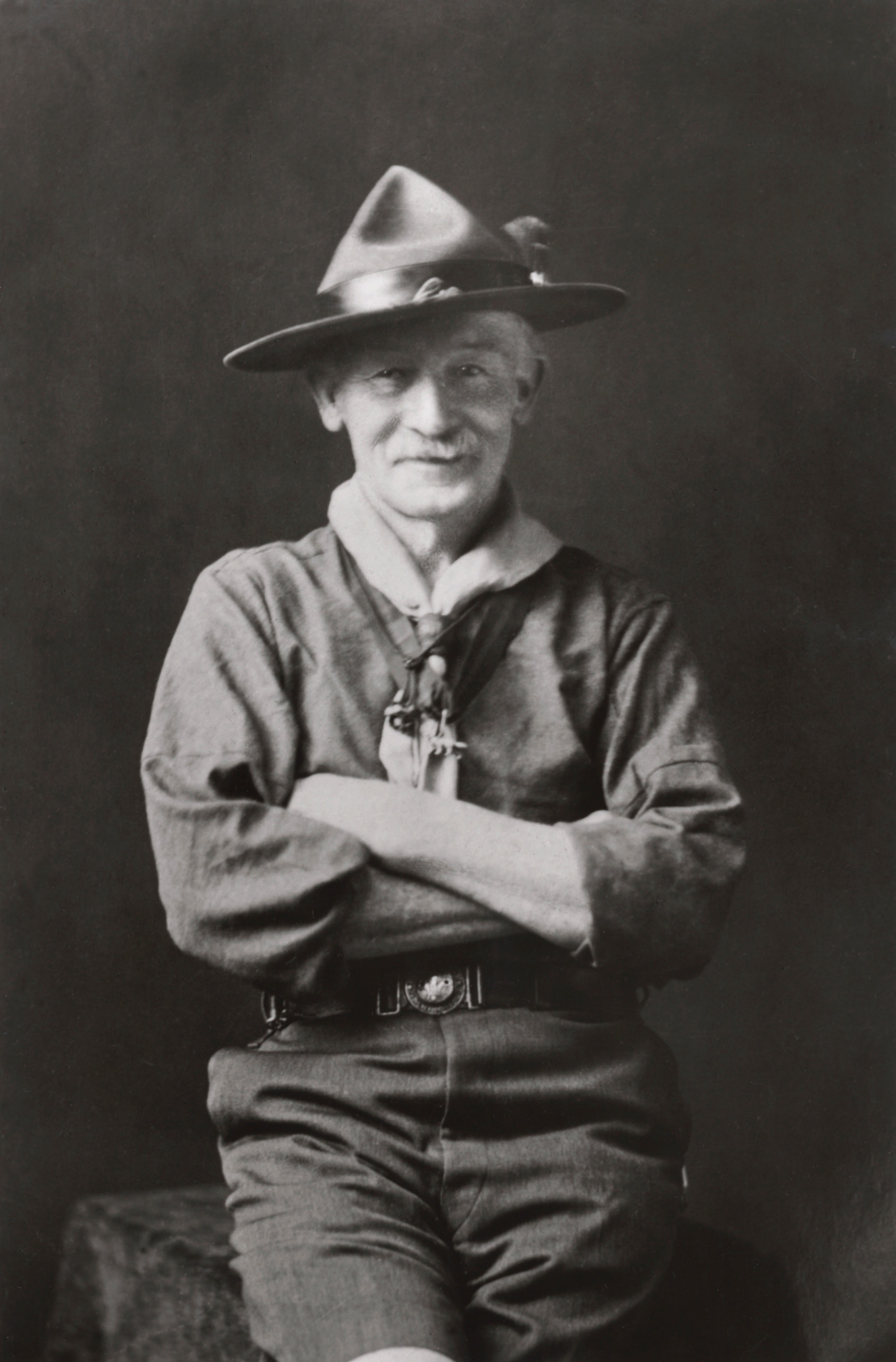

Before the Fly-Fishing merit badge was officially sanctioned in 2002, the sport had been a part of scouting’s rich history for nearly a century. The movement’s founder, Lord Robert Baden-Powell (B-P), was an avid fly fisher. He was posthumously inducted into the International Game Fish Association Hall of Fame the year the merit badge was established.2

B-P believed that a scout should know how to fish, for both survival purposes and the virtues of sportsmanship and perseverance that can be learned through its practice.3 In the Fall 1999 issue of the American Fly Fisher, museum member and Eagle Scout Douglas R. Precourt authored an informative piece, “Fishing with Baden-Powell: Stories of the Chief Scout and His Love of Angling.” In it, he informs the reader:

As the “Chief Scout” of the growing Boy Scout movement, B-P traveled the world. He oversaw the development of the organization, attended jamborees, and provided leadership and inspiration. Everywhere he went, his fly rods, reels, and fishing kit went with him so he could collect his personal “fishing fee” for the time he had given to scouting.4

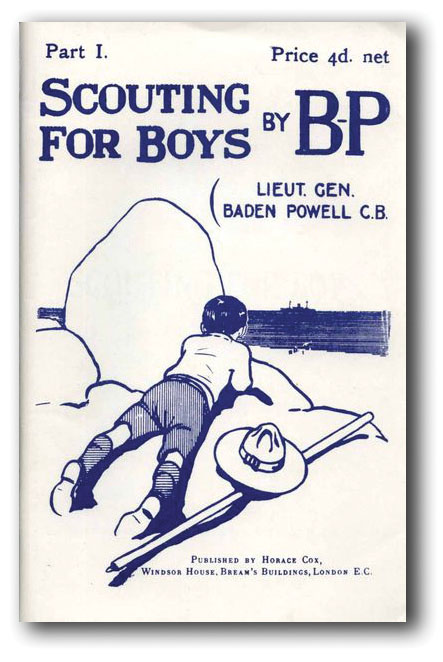

In 1908, B-P published his thoughts in Scouting for Boys. The value he placed on fly fishing was made clear when he wrote, “Fishing brings out a lot of the points in Scouting, especially if you fish with a fly . . . If you use a dry fly, that is, keeping your fly sitting on top of the water instead of sunk under the surface, you have to really stalk your fish, just as you would a deer or any other game, for a trout is very sharp-eyed and shy.”5 As the scouting movement took hold in America, fly fishing was part of it.

Those early scouts had a much more challenging task on their hands when the Angling merit badge was first introduced by the BSA in 1911. Fly fishing and rod building were key components for earning the badge. It was startling to learn how demanding the five requirements were, as well as to accept the fact that I couldn’t come close to completing them today:

- Catch and name ten different species of fish: salmon or trout to be taken with flies; bass, pickerel, or pike to be caught with rod or reel; muskellunge to be caught by trolling.

- Make a bait rod of three joints, straight and sound, 14 oz. or less in weight, 10 feet or less in length, to stand a strain of 1½ lbs. at the tip, 13 lbs. at the grip.

- Make a jointed fly-rod 8–10 feet long, 4–8 oz. in weight, capable of casting a fly 60 feet.

- Name and describe twenty-five different species of fish found in North American waters and give a complete list of the fishes ascertained by himself to inhabit a given body of water.

- Give the history of the young of any species of wild fish from the time of hatching until the adult stage is reached.6

It was interesting, but not quite a surprise, to learn that by 1913, only one scout had earned the Angling merit badge as originally constituted. The June 1913 edition of Boys’ Life contains the following announcement:

It is surprising to find that the angling badge, won by Scout Commissioner Evarts this month, is the only one of its kind that has been awarded in the history of this organization.* This is one of the best times of the year for fishing, and no sport can be more healthful than this. Why not have angling head the list next month? How about this, you fisherman scouts?7

The asterisk in the text above led to this revealing note:

The reason for this is found in the requirements of the test, which should be revised. Requirements Nos 1 and 2 [sic] might well be stricken out, as ability to make rods as specified is not, and never has been, considered a test of an angler’s qualifications. Instead, the scout should be required to pass certain tests in casting with bait or fly rod, should know the natural food of various game fishes and the best baits or lures to use in catching them, and especially should be able to tell how and where to fish for the different species. He should know how to secure various natural baits and how to fix them on his hook; how to properly land a game fish with a dip-net, whether wading or fishing from a boat; and he should have a knowledge of the propagation and protection of fish, without which to-day we would have no fishing worthwhile. —ED.8

So, who was this extraordinary scout?

Further research led me to a website, Portraits of War, which had the following information posted about native Vermonter Joseph Allen Evarts:

Originally born in Swanton, Evarts attended Norwich in 1904 and eventually joined up with the 1st VT National Guard. He was a direct descendant of the famous Allen family and can claim Ethan Allen as a great-great-uncle. He went overseas in October of 1917 with the 101st Machine Gun Battalion as a 1st LT and was promoted to Captain in August of 1918. He was assigned as Company Commander of Company D of the 103rd Machine Gun Battalion of the 26th Division. Evarts was well loved by the citizens of St. Albans and was sorely missed after he passed away in 1920 from gas-related lung complications. . . . He was cited at least two times for bravery while overseas and likely saw a lot of combat.9

Another contributor to the site added in the comments section:

Joseph A. Evarts was the 34th Eagle Scout in Boy Scouts of America and earned his Eagle Scout rank in 1913 while serving as Scout Commissioner for the state of Vermont at the age of 26. He was the first Eagle Scout from Vermont and also the first Scout ever to earn Life and Star ranks as a pre-requisite for Eagle.10

It is clear that earning the Angling merit badge was not within the reach of the average teenager; the fact that Joseph Evarts was twenty-six when he earned the first shows the level of commitment that was required. (Before 1965, adults could earn the Eagle rank.)

The merit badge was officially revised, and the following guidelines appeared in the August 1914 issue of Boys’ Life:

- Catch and name seven different species of fishes by the usual angling methods (fly-casting, bait-casting, trolling and bait-fishing). At least one species must be taken by fly-casting, and one by bait-casting. In single-handed fly-casting the rod must not exceed seven ounces in weight; in double-handed fly-casting one ounce in weight may be allowed for each foot in length; in bait-fishing and trolling the rod must not exceed ten feet in length nor twelve ounces in weight.

- Show proficiency in accurate single-handed casting with the fly for distances of 30, 40, and 50 feet, and in bait-casting for distances of 40, 60, and 70 feet.

- Make three artificial flies (either after three standard patterns, or in imitation of different natural flies), and take fish with at least two of them. Make a neat single gut leader at least four feet long, or a twisted or braided leader at least three feet long. Splice the broken joint of a rod neatly.

- Give the open season for the game fishes in his vicinity, and explain how and why they are protected by law.11

The acclaimed statesman and angler Henry van Dyke contributed an article to the same issue titled “The Scout Merit Badge of Angling: A Famous Fisherman Writes of Some Things All Boys Should Know About This Fascinating Sport.” Van Dyke wrote, “The list of requirements, I think, is a very fair one; not too hard and not too easy, and may be generally applied to all parts of the country.”12 He also advocates for the scouts themselves by attempting to shield them from a debate that was under way in the sport

Many very good anglers maintain that the artificial fly is not really an imitation of any natural insect, but that it attracts the fish largely from curiosity. I think this is certainly true in the case of salmon flies. In my opinion, therefore, the boy should be left free to choose which of the two theories of fly fishing he wishes to follow; the imitation of the natural fly, or the making of an artificial fly on one of those patterns which have proved successful in stimulating the curiosity of the fish.13

By 1951, when the badge was retired, the four requirements had evolved:

- Catch and identify at least one specimen from each of three local species of fish by usual angling methods (fly-casting, bait-casting, trolling, and bait-fishing). At least one species must be taken by fly-casting or one by bait-casting.

- Show proficiency and accuracy in fly-casting with the fly for distances of 30 or 40 feet, or in bait-casting for distances of 40, 60 and 70 feet.

- Name and describe at least five standard fly patterns, or make a fly, spoon troll, plug or any other form of artificial bait lure and prove its worth by catching fish with it. Make a neat single-gut leader at least four feet long. Splice the broken joint of a rod or in some other way show proficiency in repairing broken tackle.

- Give the open season for game fishes in his vicinity, and explain how and why they are protected by the law.14

Fishing Merit Badge (1952-Present)

When the Angling merit badge was retired in 1951, it was replaced by the Fishing merit badge, which remains a current offering. The fly-fishing requirements were reduced to an elective under the nonspecific “demonstrate the proper use of two different types of fishing equipment.”15 This reduction to an elective seems unnecessary considering that a reported total of 43,884 scouts had earned the Angling merit badge since 1913.17

Fly Fishing Merit Badge (2002-Present)

News of the new Fly-Fishing merit badge broke for me in the Fall 2001 issue of this journal in a letter submitted by Doug Precourt, wherein he states:

I was asked by the National Advancement Committee of the Boy Scouts of America to rewrite the current fishing merit badge requirements and book to incorporate fly-fishing elements and to propose the creation of a new fly-fishing merit badge for consideration. A committee was formed and the work done, and I just learned in May that starting in 2002, all scouts will have the opportunity to earn the new Fly-Fishing Merit Badge.17

Fifty years after the Angling merit badge had been replaced by the Fishing merit badge in 1952, a group of dedicated individuals established the Fly-Fishing merit badge. The American Museum of Fly Fishing is listed as a resource in the booklet.18

Complete Angler Recognition (2014-Present)

In 2014, scouts were given the opportunity to gain special recognition by wearing the Complete Angler patch. This requires earning the Fishing, Fly-Fishing, and Fish and Wildlife Management merit badges and performing a specified service activity in scouting or their community.

Scout Camps

Lord Baden-Powell first field tested the concepts he promoted in Scouting for Boys during an experimental encampment in 1907 on Brownsea Island, just off the southern English coast near Poole. That initial experiment was a success, and it eventually grew into thousands of such camps as the scouting movement took hold and expanded worldwide.

The establishment of America’s first scout camp remains a subject of debate today. Camp Owasippe in Twin Lake, Michigan, makes a credible claim as the oldest known camp. The land was purchased in 1910, the camp was constructed in 1911, and it opened in 1912. Camp Owasippe officially celebrated its centennial in 2011.19

Philmont Scout Ranch

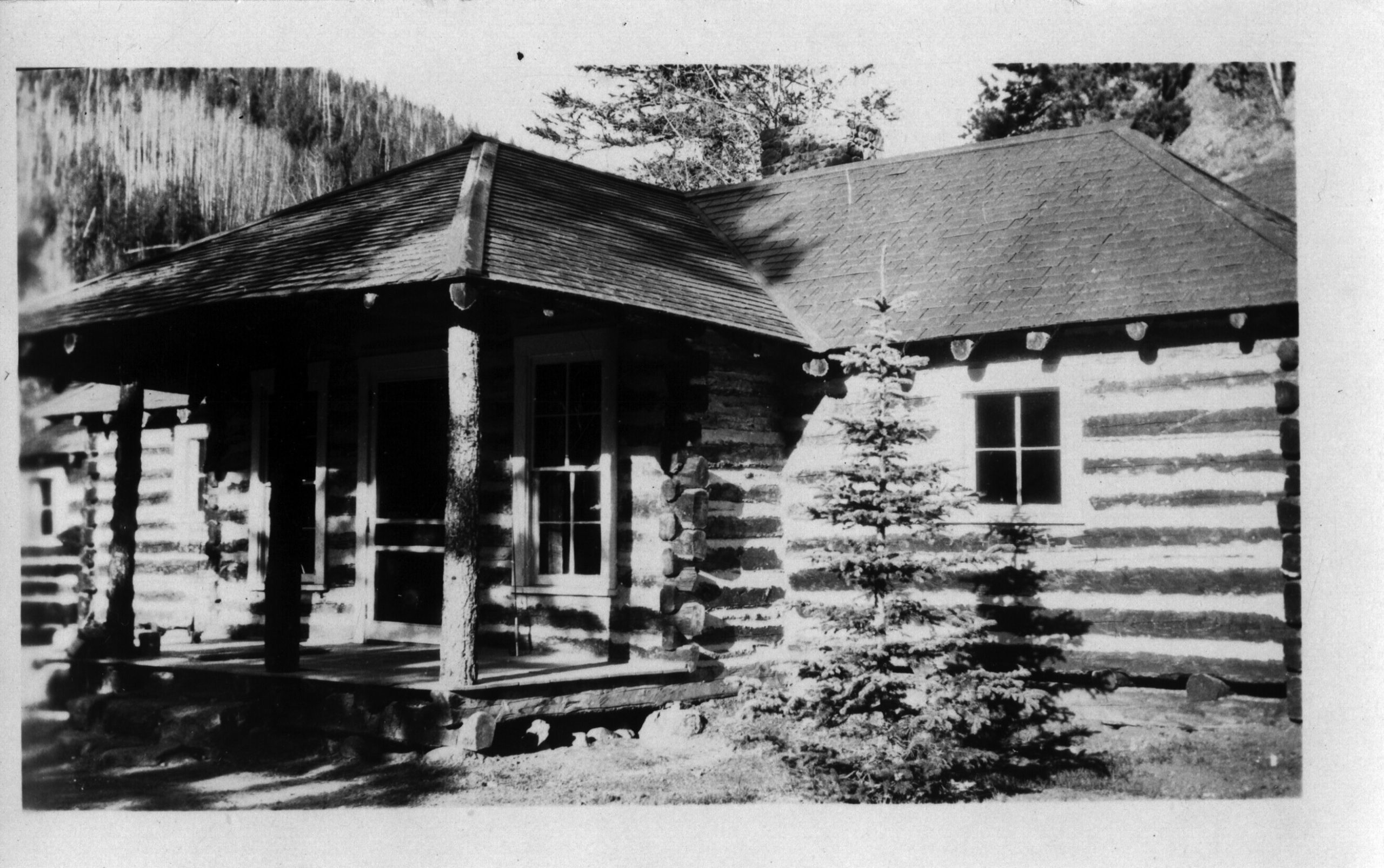

The Philmont Scout Ranch in Cimarron, New Mexico, is the big BSA camp. It was established in 1938 when benefactor Waite Phillips donated his 35,857-acre ranch to the movement. The ranch has grown to cover 214 square miles and witnessed its millionth scout step onto the property in 2014. Rayado Lodge, one of Phillips’s favorite spots on the ranch, is now known as Fish Camp. It hosts a variety of fly-fishing programs for scouts and training for their adult leaders.*

*“Philmont Scout Ranch, Boy Scouts of America, Fish Camp Profile,” Northern Tier. http://www.ntier.org/filestore/philmont/pdf /jobs/Backcountry_Fish_Camp_HW.pdf, 3. Accessed 28 March 2017.

Lake Kenosha at Camp Mattatuck

BSA Camp Mattatuck in Thomaston, Connecticut, was founded in 1939. Lake Kenosha is the centerpiece of the 500-acre property. As a scout leader, I attended camp there with Jack each summer, always with my fly rod rigged and ready outside my tent. At dawn on most mornings, I took a quiet walk down to the lake to cast bass bugs in peace for the hour or so before all hell broke loose. Then it would be a frenzy of canoes, sailboats, swimmers, and lifeguard whistles blowing throughout the day. Scouts taking their Fishing or Fly-Fishing merit badge classes filled in along the open gaps on the shoreline in their attempts to catch one of the lake’s resident bass. Many of these fish were large and aggressive, and at least once during the week a young scout would bring in a 20-incher to swim around in the nature center fish tank for a day or two before being released back into the lake.

One calm morning, the fishing was slow, and the quiet was broken suddenly by the words “Nice cast, mister.” Turning around to say thank you, I found three scouts standing attentively, tackle boxes and spinning rods in hand. One added, “Yeah, my brother likes fly fishing, but I don’t get it.” I responded, “Don’t worry, you’ve got plenty of time to try it. Take the Fly-Fishing merit badge class; it’s a lot of fun to catch a fish on a fly.” Another casually informed me that he had never seen anyone casting a fly rod from Lightning Rock before, and that I should stay off it during a thunderstorm, as it has taken a number of strikes. “Thanks for that tip,” I replied, and filed a very useful piece of information away. With that, the scouts turned and rambled off down the trail.

Helping teach the Fly-Fishing merit badge course is its own test of “infinite patience”20 as you watch the scouts tying and untangling knots, smacking the camp’s fly-rod tips back and forth on the grass, and winding away at tying their first flies. The catch-and-release ethic we teach today was also a tenet found in Scouting for Boys generations before the practice became widely adopted.21

Now I’ll take the liberty of sharing one personal reflection on fly fishing and scouting. It was my first summer at Camp Mattatuck, and I was casting a popper off the dock near the camp chapel. It was a quiet morning, the lake was still, and it was all mine. From the far side, a group of adults and scouts could be heard plodding loudly down the hill from their campsites, gravel crunching and tackle boxes rattling. They must not have realized how easily sound travels across water, and the words, “What? This guy is fly fishing?” were followed by some mocking giggles. At that moment I believed that if there were truly any justice in this world, my fly would land just off the lily pad and an angry bass would slam it with fury. Fate did its part. The popper landed where it was supposed to, two quick strips produced the necessary disturbance, and the water exploded. A good bass was on, and I let it run freely so my reel could make as much of a whir as possible. They all came running to watch as I reeled in the 17-incher and nonchalantly released it. Feigning that it was routine, I bid them “Good luck,” and headed off. The sin of pride aside, I was pleased to have had the opportunity to protect the integrity of the sport at a place where fishing has always been practiced.

The Boy Scouts of America have been keepers of the flame since its formal establishment in 1910 and introduction of the Angling merit badge in 1911. Fishing, fly fishing, and the ethics of good sportsmanship have been practiced by both scouts and adult scouters throughout the movement’s history. The BSA National Camping School offers courses for adults to become certified angling instructors to help scouts receive the proper introduction, guidance, and practical experience necessary to earn their Fishing and Fly-Fishing merit badges.

Nationwide, scouts have the opportunity to fly fish at the hundreds of camps that are attended each summer or for a full week at a specialty fly-fishing camp. We often hear that we need to ensure that the next generation becomes inspired to carry on the sport, the enjoyment, and the legacy of fly fishing. Thankfully, the BSA has always honored the sport and continues to do so. Who knows? Maybe the next time you visit the American Museum of Fly Fishing, you’ll see tents pitched out back by the pond with scouts flailing away with their rods, tying flies, and untangling knots along the way to earning their Fly-Fishing merit badges.

Endnotes

- Boy Scouts of America, Merit Badge Series, Fly-Fishing (Brainerd, Minn.: BANG, 2009), 2–3.

- “Lord Robert S. S. Baden-Powell: IGFA Fishing Hall of Fame,” International Game Fish Association, https://www.igfa.org/Museum/HOF-Baden-Powell.aspx. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- Lord Robert Baden-Powell, Scouting for Boys (London: Horace Cox, 1908), 114–15.

- Douglas R. Precourt, “Fishing with Baden-Powell: Stories of the Chief Scout and His Love of Angling,” The American Fly Fisher (Fall 1999, vol. 25, no. 4), 17.

- Baden-Powell, Scouting for Boys, 114–15.

- Boy Scouts of America, Boy Scouts Handbook, 1st ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1911), 24.

- A. R. Forbush, “The Honor Roll,” Boys’ Life (June 1913), 33.

- Ibid.

- “WWI 26th Yankee Division, 103rd Machine Gun Battalion Vermont Dog Tag Grouping,” Portraits of War, 29 May 2012. https://portraitofwar.com/2012/05/29/wwi-26th-yankee-division-103rd-machine-gun-battalion-vermont-dog-tag-grouping/. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- “8th Vermont Infantry Regiment Civil War Soldier: Henry N. Derby Dies of Disease in Louisiana,” Portraits of War, 6 June 2015. https://portraitofwar.com/2012/10/01/8th-vermont-infantry-regiment-civil-war-soldier-henry-n-derby-dies-of-disease-in-louisiana/. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- “The Requirements for the Merit Badge of Angling,” Boys’ Life (August 1914), 12.

- Henry van Dyke, “The Scout Merit Badge of Angling: A Famous Fisherman Writes of Some Things All Boys Should Know About This Fascinating Sport,” Boys’ Life (August 1914), 11.

- Ibid.

- “Angling.” MeritBadgeDotOrg. https://meritbadge.org/wiki/index.php/Angling. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- “Fishing.” MeritBadgeDotOrg. https://meritbadge.org/wiki/index.php/Fishing. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- “Angling Merit Badge History,” Scoutmaster Bucky. https://www.scoutmasterbucky.com/Scoutmaster-Bucky-Merit-Badges -Angling-History.htm. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- Doug Precourt, “Fly-Fishing Scouts” (letter), The American Fly Fisher (Fall 2001, vol. 27, no. 4), 32.

- Boy Scouts of America, Merit Badge Series, Fly-Fishing, 95.

- “History,” Owasippe Scout Reservation. http://www.owasippeadventure.com/history/. Accessed 28 March 2017.

- Baden-Powell, Scouting for Boys, 115.

- Boy Scouts of America, Boy Scouts Handbook, 109. The catch-and-release tenet reads as follows: “It should be the invariable practice of anglers to return to the water all uninjured fish that are not needed for food or study. ‘It is not all of fishing to fish,’ and no thoughtful boy who has the interests of the country at heart, and no lover of nature, will go fishing merely for the purpose of catching the longest possible string of fish, thus placing himself in the class of anglers properly known as ‘fish hogs.’”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2017 (Vol. 43, No. 3) issue of the American Fly Fisher.