BY RICHARD G. BELL

The World’s Columbian Exposition

The World’s Columbian Exposition was created by an Act of Congress on 25 April 1890. Section 1 of this enabling act stated as follows:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, that an exhibition of arts, industries, manufactures, and products of the soil, mine and sea shall be inaugurated in the year 1892, in the City of Chicago, in the State of Illinois, as hereinafter provided.1

It was short notice for an undertaking of such magnitude. The Exposition was to mark the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America and celebrate the progress of civilization in the new world. The time was propitious. By 1869, the railroads had already stretched their thin, slender bands of steel across the country. The vast open spaces were being traversed, explored, staked out for claim or homestead, and then bypassed by the rolling tide of American expansion. For almost three hundred years, the frontier had been the dominant fact of American history and the dominant theme of its culture. By 1890, the year when the last agonizing spasm of the Plains Indian wars flickered and died at Wounded Knee, the frontier was pronounced closed.2 We had fulfilled our national destiny. We knew, geographically, what we were and how far we extended in every direction, and had inordinate pride in what we had done to make the country. It was time to collect its wonders and show them off to the world.

Interestingly, it was also a time that marked the growth of an emerging conservation movement. Much of wild America had been transformed, and it was becoming widely understood that what was left was both finite and fragile. Thus, in 1892, the Adirondack Park was created in New York State,3 and across the country in California, the Sierra Club was founded.

A commission to be appointed by the president of the United States was assigned the task of organizing the Exposition and implementing the Congressional mandate.4 It did its work diligently. Notwithstanding the need for an additional half year of preparation, a magical new city within a city–more than two hundred buildings of all sizes–quickly blossomed on Chicago’s Lake Michigan waterfront. A midway, exceeding half a mile in length, led visitors in from Cottage Grove Avenue to the main exhibition site. In all, the site was an enormous 633 acres. To see everything quickly, it was estimated that it would take about three weeks, and one would have to walk 150 miles. It would be the first city in history that, when President Grover Cleveland pressed a switch, would be bathed in the miracle of Edison’s new electric light. This he did on 1 May 1893 to the cheers of 150,000 spectators. It was simply breathtaking, and it dazzled the world.5

Picture A:

Looking down the Midway toward George Ferris’ enormous wheel, which could carry sixty people to a car. A “captive balloon” is shown on the left, safely tethered to the ground. From James W Shepp and Daniel B. Shepp, Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed-Being a Collection of Original Copyrighted Photographs Authorized and Permitted by the Management of the World’s Columbian Exposition-Published by Globe Bible Publishing Co., Chicago, Ill.; Philadelphia, Pa. (1893).

Picture B:

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody sought to exploit the Exposition’s crowd appeal by setting up his Wild West show adjacent to the access Midway. From Rand, McNally & Co.’s A Week at the Fair (Chicago,1893).

The Event

Imagine a five-month Super Bowl, Mardi Gras, Coney Island holiday, and Olympics rolled into one. It included majestic white buildings for generic classes of exhibition, with multiacre floor space, such as the Machinery, Electricity, and Agricultural Buildings. The United States Government Building itself occupied a 4-acre site. The nations of the world were invited, and seventy-seven attended as exhibitors, eighteen of them having their own exclusive building sites. Thirty-six states of the union had their own buildings as well, as did the combined territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. Private industry sites and exhibitions were encouraged, and the response was equally enthusiastic.

The long midway served as an access promenade from downtown Chicago to the exhibition area and to the major buildings that were clustered around a lagoon carved out of Lake Michigan. Spectators were lured into the midway by wonders and adventures ranging from a Lapland Village and an Electric Scenic Theater to a 10-ton Canadian cheese and a life-sized, chocolate Venus de Milo. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody–himself not an exhibitor but no stranger to razz-ma-tazz–shrewdly sought to capitalize on the Exposition’s drawing power. He rented lots just south of the midway, where he constructed an eighteen-thousand-seat covered grandstand. Cody offered, in addition to his usual cowboy and Indian show, both “Genuine Russian Cossacks from the Caucasus” and “Genuine Arabs from the Desert.”

Stationed at the western end of the midway was an international military encampment where soldiers of the visiting nations could strut their stuff. Almost directly opposite, a mile and a half away, was a replica of the battleship U.S.S. Illinois riding at anchor in Lake Michigan. Perhaps grimly foreshadowing the future, the Krupp Works from Essen, Germany, paraded the top of its new line: an enormous cannon that could throw a 1-ton projectile well beyond the horizon.

You could do almost anything and indulge almost every appetite. If you tired of the endless and wondrous exhibits, perhaps a dip in the natatorium would revive you, or an enjoyable ride on the electric train, the world’s first. Better still was G. W. Ferris’s gigantic wheel. Mounted vertically, it was 250 feet in diameter and packed sixty people to a car for the heart-stopping ride of their lives. For a rest, one could listen to live concerts from New York by way of the magic of Mr. Bell’s telephone. Or, if the missus stayed at home, one might sneak a peek at “Little Egypt” behind her diaphanous veils, doing a “genuine native muscle dance,” soon known to the regulars as the “hootchy-kootchy.” Refreshment concessions were everywhere, such as that of J. H. Dilworth & Co., which offered something called “Temperance Drinks” for those so inclined. In short, there was something for everyone. “Sell the house if necessary and come,” one awestruck spectator wrote home. “You must see this fair.”6

"And Come They Did..."

And come they did. In all, twenty-five million spectators were drawn to the White City before it closed in October 1893, with more than two million showing up during each of the last three weeks. It was a rip-roaring, resounding success, worth it even if, as one tired spectator said, “ . . . it did take all of the burial money.”7

One of the major exhibition sites was the Fisheries Building; after all, the enabling act specifically provided for exhibitions of “ . . . products of the . . . sea.”8 It faced upon the lagoon, directly opposite the U.S. Government Building. It was designed by architect Henry Ives Cobb, in what was referred to as the Spanish Romanesque style. Light, airy, and appealing, it was quite properly described as an “architectural poem.”9 It consisted of a central edifice 365 feet in length and 165 feet wide, with two polygonal satellites, each 133 feet in diameter, attached by handsome arcades at its east and west ends. In all, it was more than 1,000 feet in combined length, with more than 3 acres of floor area. The Congressional mandate was broadly construed, and the building had both fresh- and saltwater circulating capacity to display the wonders of not only the sea, but of the lakes, rivers, and streams of the world as well. The easterly polygonal had both a fresh- and saltwater aquarium. In addition, the commercial business of fishing was featured along with sportfishing, and some space was specifically reserved in the westerly polygonal for private sporting tackle makers to display their wares. One of these was the Charles F. Orvis Company of Manchester, Vermont.

Charles F. Orvis was an archetypical Yankee businessman-craftsman. Born in Manchester, Vermont, in 1831, he was technically adept, thoughtful, and thorough.

Orvis and the Standardization of Fly Patterns

Charles F. Orvis was an archetypical Yankee businessman-craftsman. Born in Manchester, Vermont, in 1831, he was technically adept, thoughtful, and thorough. He tinkered with toys and clocks in his youth. He founded his fishing tackle company in 1856. He obtained his first patent on a perforated fly reel (1874), which became the precursor of modern lightweight American reels. It came in a handsome walnut box and sold for $2.50. The company’s early rods were white ash and lancewood, but Orvis was using bamboo by the late 1870s. The early Orvis products were of a standard of quality that would be the hallmark of the company to the present day. By 1884, Orvis was selling rods and reels and other fishing tackle far beyond Manchester by mail-order catalogue. In 1893, the company was probably as well known for its trout flies as for any other product and was anxious to expand this product line to national markets through catalog distribution.10

By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, fly fishing had grown in popularity. It was no longer just an eastern sport. The movement of the American population west, the penetration of wild areas by the railroads, and the growing circulation of the sporting magazines and catalogs like Orvis’s contributed to the sport’s national appeal. Consequently, the demand for effective flies was also rising. That was the good news. The bad news was that there was no rhyme or reason to the standards of American fly patterns, and different regions of the country zestfully pursued their own imaginations. There could be no assurance that the standard patterns effective on the Battenkill would be even recognized on the Beaverkill, much less the Brule. Charles Orvis sought nothing less than to organize and standardize fly patterns across the country. He explained his problem and his proposed solution to a friend in 1885:

I had for many years made fishing rods and reels, and in filling orders for the same, had frequent requests for other tackle to be sent in the same box.

I then ordered, to supply these demands, small quantities of flies from dealers–first ordering a complete line of samples with the names attached.

These I received, but soon found it utterly impossible to duplicate my orders. I was continually disappointed by the substituting of other flies or sizes than the ones I had ordered, and in turn, I was forced to disappoint and apologize to my customers. I then thought that if there was any way out of this dilemma, caused by a confusion in names and a carelessness in copying exactly the pattern fly, I should seek it out.

In time, one of my family viewed with favor the idea of learning to tie flies. To this end, I employed one of the best fly tiers in the city to come to my house and stay until he had imparted his knowledge and skill, and when I felt that we were competent, I advertised to fill orders exactly in accordance with a customer’s wishes.11

A Woman’s Touch

Mary Orvis was born in 1856, the year the company was founded, and was the only daughter among Charles Orvis’s four children. She had shown an early interest in flies, and Orvis had brought John Haily, an expert fly tyer, up from New York to teach her the art. Mary married John Marbury in 1874, but the marriage did not last, and they quickly separated. Sadly, their only child died in infancy. When the time came to find someone to take charge of the company’s expanded fly opportunities, Orvis had no hesitation in turning to Mary. With six female assistant fly tyers as her staff, she went to work in 1876 in the second story of the white clapboard company building, which still stands on Union Street in Manchester.12

To understand his market, and to help his market understand the company, Charles Orvis had the idea of corresponding with fishermen around the country. Hundreds of letters were sent asking the recipients to comment on their favorite flies for their regions of the country. An astounding 201 responses were received, from or with respect to thirty-eight states altogether, ranging from Maine to California, as well as Canada. These were carefully cataloged by Mary. They answered the questions asked, and more, for fishermen are a loquacious lot. Some, predictably, could not refrain from elaboration. W. David “Norman” Tomlin of Duluth, Minnesota, for instance, was soon into one of his favorite fish stories: “He ran out thirty yards of line before showing any sign of his size; as I checked him, he came to the surface, salaamed, and started on a new gait . . . ”13

Mary presided over the process that–as Charles Orvis had hoped– incorporated these correspondents into an extended fly-fishing family. C. S. Wells of Victoria, Texas, shrewdly anticipated the end product when he said, “Your idea of collecting information in regard to the use of flies in different sections is a good one, as, if the material thus received is compiled and published, it will be very interesting reading for anglers.”14

Compiled and published it was, in book form under Mary’s thoughtful and artistic supervision. It was, and remains, a masterpiece. Favorite Flies and Their Histories first appeared in 1892, the year the Exposition was supposed to open, and went through eight more printings by 1896 (and two more since then). It cataloged with historical and technical precision 233 trout and salmon fly patterns and an additional 58 bass patterns. It is widely held that the book, more than anything else, both standardized fly patterns and set the standards for future development.15 What gives the book its special and lasting appeal are the thirty-two color plates of fly illustrations in vivid chromolithography. The flies, tied under Mary’s supervision and used as models for these illustrations, are carefully preserved today at the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont. They alone are worth the trip. Their discovery by Paul Schullery deserves retelling.

One day, not long after my arrival at the American Museum of Fly Fishing as its new director, I was exploring some of the shelves of the collection’s storage room. I came across a large, handsomely made but obviously aged box=cedar it appeared to be=that didn’t seem to be a tackle box or any other type I might have recognized. Carefully lifting the hinged top, I saw what seemed to be the top end of dozens of small mortised picture frames. Each end had written on it, by hand, some phrase, such as bass dd or trout q. When I slid one from the box, I saw one of the, if not the, greatest treasures in the history of American fly fishing: the original flies, mounted in appropriate order, from which the chromolithographs in Mary’s book had been made.16

It was a natural progression for the Orvis Company to become an exhibitor at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Space had been specifically reserved for tackle manufacturers in the west polygon of the Fisheries Building. Besides, publication of Favorite Flies and Their Histories had given Orvis a new level of national prominence, and there could be no better place from which to exploit that than the Exposition in the City of Light. The Orvis exhibit would, of course, include and feature Mary’s elegant flies.

The exhibit consisted of wood-framed panels containing fishing photographs mounted on both sides. Each panel, measuring approximately 29½ inches tall by 24 inches wide, included a selection of meticulously tied Orvis flies. The panels were mounted vertically, in groups, and were hinged around a central post or spine and turned for viewing as one would turn the pages of a book. Forty of these are preserved at the American Museum of Fly Fishing, and they are displayed as twenty two-sided panels, ten over ten.17 Generally, each panel contains region-specific photographs and flies, but this is not uniform, and some contain photographs and flies from several regions. The photographs, enhanced by handwritten captions, are all more than one hundred years old. They are fading now. Not all were of high quality by modern standards to begin with, but allowances must be made for the state of the art at that time. Notwithstanding, some are striking and represent the high state of naturalist photography in the 1890s. In all, fifteen photographers have been identified, including William Henry Jackson and Seneca Ray Leonard. Their professional addresses range from Bangor, Maine, to San Francisco, California, giving a sense of the range and popularity of fly fishing at that time.

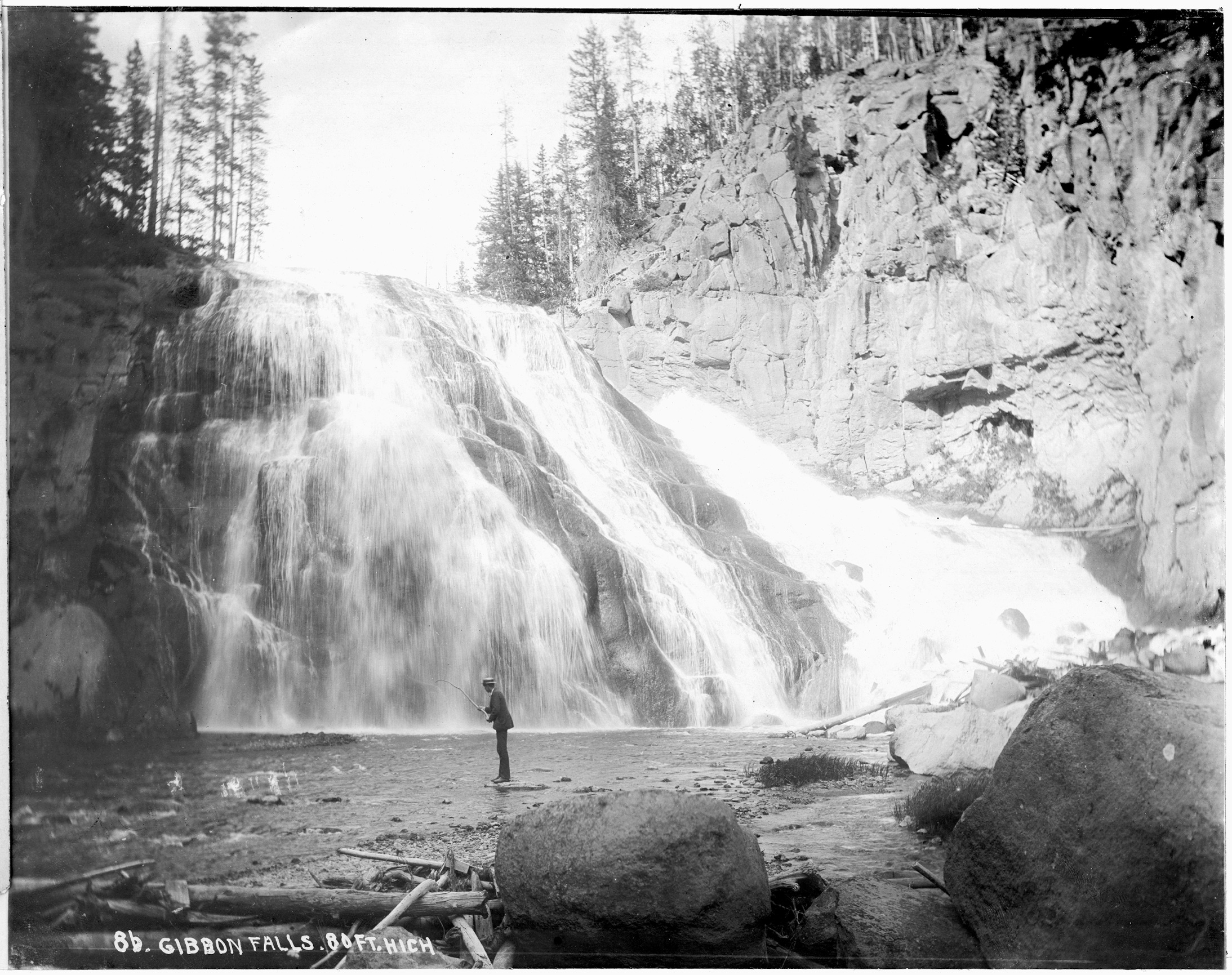

The sites of the photographs range from the familiar (especially to the Orvis family) banks of the Battenkill in Vermont to the Beaverkill, Upper Ausable Lake, and the Saranac River in New York; Parmachenee Lake in Maine; the Nipigon and St. Marguerite in Ontario; the Brule in Wisconsin; the St. Croix in Minnesota; the Frying Pan and the Rio Grande at Wagon Wheel Gap in Colorado; Yellowstone Lake and Gibbon Falls in Wyoming; Eaton Creek on the upper Missouri in Montana; the Clackamas and Willamette in Oregon; Lake Tahoe and the Merced in California; and finally, in a long reach for largemouth bass, to Sebastian Creek and the St. John’s River in Florida. The photographs are an impressive contemporary view of wild America at the turn of the twentieth century. But they are much more than that: they are a nostalgic memory of how things used to be in our sport, before the full advent of the automobile and the strip mall. It is a mistake to think these lovely scenes were, even then, totally unspoiled; they are not. Lumbering had long left its scars on many watersheds. Unregulated fishing and pollution had decimated native brook trout populations in the Adirondacks and Catskills. But compared with today, compared with the environmental assaults of the years after 1893, these photographs give anglers a sense of how glorious it was when our American sport was young. That these photographs are graced by Mary Orvis Marbury’s elegant flies makes them even more endearing, for her flies are, indeed, the jewels in the crown at the American Museum of Fly Fishing.

Endnotes

- 26 Stat. 62 (1890), Fifty-first Congress Sess. I Ch. 156, 25 April 1890; Hereinafter called the “enabling act.”

- Frederick J. Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History (Readex Microprint, 1966), 199.

- William Chapman White, Adirondack Country (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1985), 218. Constitutional protection of the Forest Preserve came in 1894. Ibid., 218–19.

- The Commission–described in Section 3 of the enabling act–consisted of two appointees from each of the states and territories, and two from the District of Columbia, as well as eight at-large appointees. Interestingly, Section 6 of the act also “authorized and required” a board of “lady managers in such numbers and to perform such duties as the Commission may prescribe.” That section went on to provide that this board could appoint one or more members to all committees authorized to award prizes for exhibits “. . . which may be produced in whole or in part by female labor.” That women’s issues, suffrage or otherwise, were in the air is further demonstrated by the Women’s Building at the Exposition, designed by Sophia G. Hayden of Boston, a graduate of MIT. This displayed such wonders as a model kitchen with a tile floor and a gas stove, which prompted the observation by Mrs. Potter Palmer, president of the Board of Lady Managers and noted Chicago society doyenne, that “women as a sex have been liberated.” Princess Eulalia of Spain, the king’s aunt, tried to prove this claim by smoking cigarettes in public (from National Geographic Society, We Americans (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1975), 296.

- Ibid., 294.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Enabling act, Section 1.

- John J. Flynn, Official Guide to World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago: The Columbian Guide Company, 1893⁾, 59. The same source reports that “the details of ornamentation [were] worked out in a realistic manner after various fish and marine forms.” See also Rand McNally & Co., A Week at the Fair (1893), 162.

- Paul Schullery, American Fly Fishing: A History (New York: Nick Lyons Books, 1987), 67–68; Ernest Schweibert, Trout (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1978), 930–31, 996.

- Schwiebert, Trout, 996, 998. It is to Mary that we owe the graceful practice of naming all flies, rather than assigning them numbers, a competing method that might have otherwise gained ascendancy.

- Schullery, American Fly Fishing, 75; see also the foreword by Silvio Calabi in Mary Orvis Marbury, Favorite Flies and Their Histories (Secaucus, N.J.: The Wellfleet Press, 1988).

- Marbury, Favorite Flies and Their Histories, 369, 371.

- Ibid., 423.

- Schullery, American Fly Fishing: A History, 75.

- Ibid.

- I have been unable to confirm precisely how and how many of these panels were displayed at the Exposition. I have seen a photograph that shows a very similar display, in the Fisheries Building, of two groups of like panels, each of about ten, mounted one above the other. There may be more not shown in this photograph, which, in any event, I can’t positively identify as the Orvis exhibition. I have no reason to believe otherwise than that all twenty were displayed, much as they are currently displayed at the American Museum of Fly Fishing.