by Jimmy Watts

On late evenings like this one I’ll collapse into bed, still dressed and dirty and too tired to change. I smell of woodsmoke and bamboo, and my long sleeves are soaked wet with creek water. Most of the time, these bedtime stories of mine tell themselves. Nights often end this way after countless days saturated by water and fire, which together have held an elemental stay over my forty-one years. I’ve been weathered by them both, these two old gods, wrinkled and blistered and polished. In their joint custody, they raised me and brought me up in a wet world that burns.

For quite some time I’ve been a fireman in a big city and a bamboo fly-rod maker in a small one. Two halves of one whole, and it is a life lived with both feet always in the water. Sometimes the water is cold and clear and falling down freestones, and sometimes it’s the boiling black water from a fire hose cascading back down a dark stairwell with flames rolling overhead. The black water in the hose first fell from clouds over the Cascades. It flowed down the Cedar River and into the big city’s water mains before being pumped from the corner hydrants. Oftentimes after leaving the firehouse I’ll fish this river that flows into our hydrants. Sometimes I fish it before and it becomes a river I stand in twice.

Sometimes, though, the river itself catches fire and evaporates into the sky and I can never seemingly stand in it again. This is such a story. Of course, the beginning of any story is arbitrary, and tonight’s bedtime tale is no different. It picks up around the time my two halves became acquainted, years ago, though I was then unaware that a storyboard was piecing itself together. It begins when a creek back home caught fire, in Bellingham, Washington, and a young man is standing in it casting his fly rod. His name is Liam Wood. His story is one we should all remember, and his river is one we should all try to stand in twice.

This evening I’m at my rod-making bench looking out past the back of the house. The day’s end is beginning, and I have an audience of evergreens resting behind a creek in the tired light of dusk. A reprise lingers over the water, perhaps the coda, holding onto the last note of a song. There is an 8-foot-long culm of raw bamboo across my lap soon to become a split-cane fly rod. It will be a totem or temple or another limb anchored to the heart of whoever holds it with a line drawn deep into the clean water it reaches toward. This rod I’m making tonight, when it’s complete, will have Liam’s name inscribed along the spine, handwritten in black india ink that bleeds into the cane fiber and becomes a part of it.

Within an arm’s reach of me, on the bench, is an old hand plane, a splitting knife, and a file. A book of wooden matches is in my breast pocket, and all the utilities of the trade are here. Off to my side, spools of thread float in a wine glass of last night’s Malbec, the hair-thin white silk turning the color of blood not yet at the lungs. This thread will wrap guides onto the rod and telescope to a wet world that was all at once an ocean and a cloud and a raindrop and a tear. Also nearby is a not-forgotten cup of yesterday’s coffee. A black level ring is haloed above its petroleum sheen as it reflects the day’s last slights of light. Spools of silk swim in here too and soak up the oily and cold dark.

In the fire pit just outside, I lit some kindling a few moments ago. In another hour, the hemlock I bucked and split last spring will be a heap of coal hot enough to temper this bamboo for Liam’s fly rod, a rod that’ll witch out of time and lean in toward wonder.

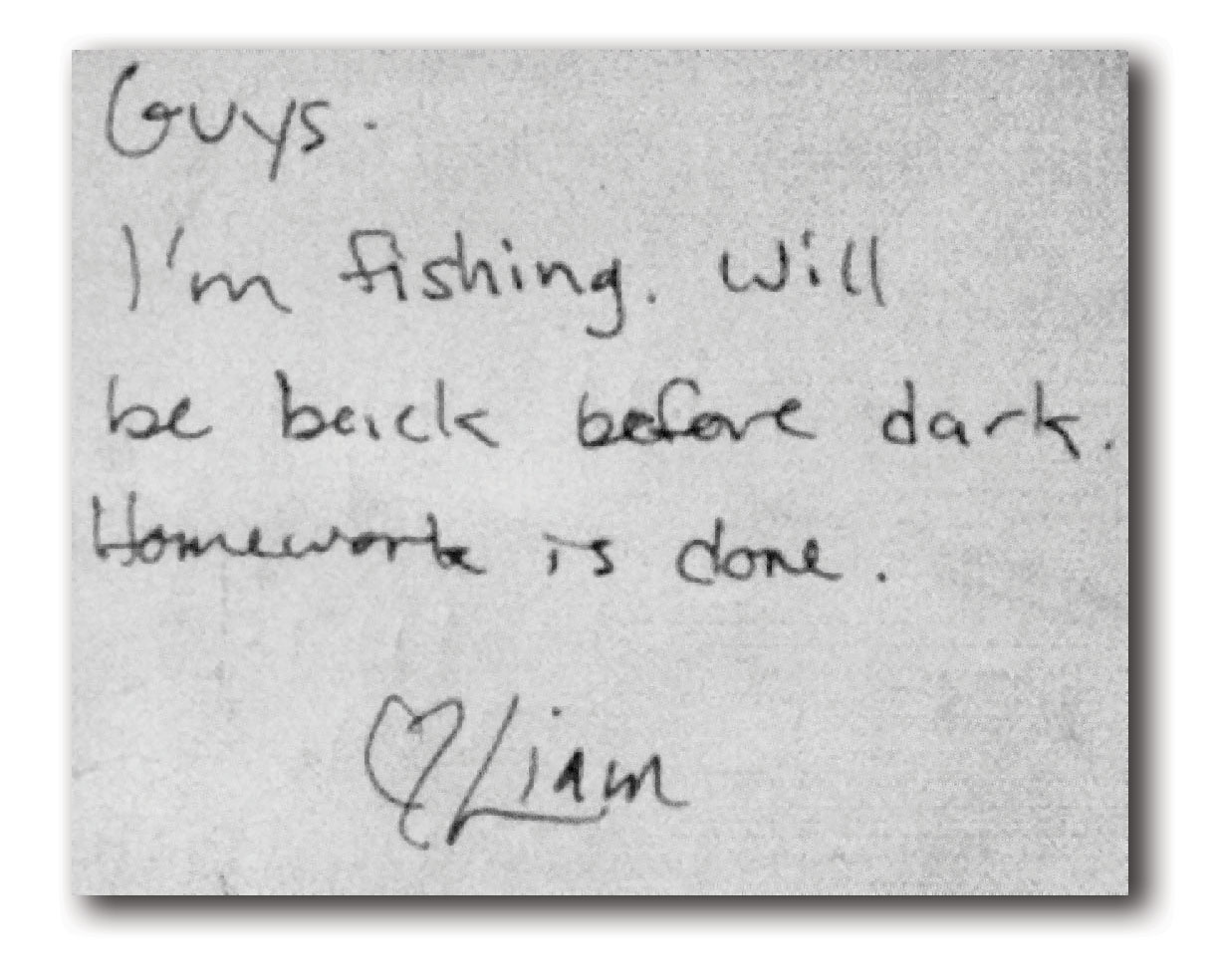

The photograph of Liam Wood’s note that hangs near the author’s workbench. Courtesy of the Wood family.

The walls around my workbench are adorned with hangings that I love, but the window trim in front of me is left void except for one solitary photograph tacked inside it at eye level.

It’s a note from eighteen-year-old Liam to his parents, one he wrote often and sometimes left on top a worn-out copy of David James Duncan’s The River Why, a book he’d read eight or nine times.

Liam worked an after-school job at a fly shop in Bellingham. He was born for water and reached out for the cold and clean and reeled it all back in. Even as a child he tied flies and read water and studied streams. For his ninth birthday his mom took him to a fly shop. By age fourteen, fly fishing enveloped the world he inhabited, and he was as natural to it as the grass that grew in the streambeds he stood in.

His heart beat on the banks of the blue and green that flowed over freestones until the time the note he wrote his parents was wrong and he was not back before dark. The time he was killed with a fly rod in his hand. The time 237,000 gallons of unleaded gasoline spilled from a ruptured pipeline into Whatcom Creek, where he was fly fishing, and exploded. It was 10 June 1999, just a few days after he graduated from high school. It was just a few days after I popped into the store where he worked to pick up a box of hooks and some hackle and hear the hatch report from this always-kind kid standing behind the counter.

Here at my bench and still looking out, it’s not quite dark. The fire in the pit outside is laying down and humming an origin song that will soon draw me into the darkness. This northern latitude and the recent summer solstice split the days wide open with an almost endless length of light. Twenty feet past the house runs a small creek that flows from a spring a mile up the mountain. It’s a creek you can’t find on a map and it winds through the woods to a pond just below our house, where frogs and fish mingle and countless generations of mallards make their first swim. Heron, wood duck, and owls frequent this little wetland puddle. My young boys skip rocks across it. They call it Lost Creek, but this is where we always find them. I once watched my nine-year-old hold company here with a great horned owl for nearly half an hour just feet from each other, and I wondered which one was there first.

About 3:30 in the afternoon, 911 calls started coming in from people reporting a fuel odor in Whatcom Falls Park. The first firefighters to arrive at the Woburn Street Bridge saw pink and rainbow fuel free flowing in the creek underneath and gas fumes floating up to the treetops, blurring them in a fog. They began to evacuate the forested park within 200 feet of the creek, working upstream to find the source of the leak.

The unleaded gasoline spilled from a neglected pipeline and filled 1.5 miles of creek through the wooded 241-acre park. Around 5 p.m., it burst into a miles-long fireball. One fireman thought a jet engine was flying low and loud overhead until he felt heat pressing against his back. The inferno roared down the creek, taking Liam’s life with it and taking the creek with it too.

Liam’s closest friends believe that once he noticed the gasoline at his feet, he followed it upstream to investigate, instead of running away. The theory fits with his nature, but he was alone, and so leaves behind questions that will never be answered and can’t be. Only the creek knows exactly what happened to Liam that afternoon, and why. All anyone knows for sure is that he was killed holding a fly rod and that he was found face down with his arms outstretched across the freestones.

We also know that the coroner decided the cause of death was from drowning and not burns from the fire. From this we know the gasoline fumes first would have rendered him unconscious. They would have made him dizzy and unbalanced and, as if to pray, caused him to drop to his knees. For a moment after, he might have looked around and briefly looked skyward, seeking an orientation and an explanation before bowing forward and falling into the water. His final inhalation was a breath of creek water passing past gills he hadn’t yet acquired, with his arms open, as if to embrace this place. As he lay there, his creek flowed over him, and in its final heroic moment, the water he loved so much shielded him from the coming flames.

Liam was discovered by search crews around 9 p.m., lying in what little water remained. Gone was the blue and green. Gone was the cold, the clear, and the clean. Gone was the endlessness of running water that once fell as rain. The almost dry creek stopped flowing. They found him in the canyon below Whatcom Falls, a favorite spot of his and near where his family told firefighters he’d likely be.

For nearly three days after he was recovered, wisps of smoke still sent up their ash and signals. It was three days before the smoldering banks surrendered to the creek, now flowing again through charred timber and coal and past a ghost casting on its banks.

At the firepit it is now dark. Night has arrived. The flames are ebbing to an orange and blue over black coals. I’m turning the long culm of bamboo in the embers, bringing the cane up to temperature. The heat drives out the moisture and bakes the sugar inside the fibers to a ligament more tensile than steel. Scorch marks sear the outer sheath.

By now the bamboo is so hot I have to wear two pairs of leather gloves to handle it. The water content inside is spitting and spilling out the ends of the culm, boiling up and out of the long cellulous fibers that run the length in its entirety, fibers that once touched the ground an ocean away and pulled the earth in. The sweet cane steam smells of fresh candy, and it curls in thick with the rising smoke of the fire, floating all the way up to a sky now full of stars.

Without fire, this cane would be just a willowing blade of cut grass, lifeless and incapable. The cane fly rod needs this kiln or would otherwise lack the resiliency to return from a weighted bend to straight. It would lack the lever action that allows an 8-foot-long, 3-ounce split-cane fly rod to deliver a dry fly over 100 feet of cold water to a rise.

There are other ways to apply heat and temper bamboo for a fly rod, but because I’m a big city fireman with burn and skin graft scars of my own, I choose to hold it over an open flame. For nearly twenty years I’ve chased fire through the tenements and townhomes and warehouses of Seattle. Hundreds of times I have laid down in Cascade hose water with a river of fire above, ever to remember young Liam who once did the same. I’ve searched him out and carried others like him out of scorched hallways and burnt timbered homes and they were all strangers to me with names being screamed out by someone standing helpless and out of reach on the sidewalk.

I carry Liam’s story with me all the time, hearing it most often with a split-cane fly rod in hand—a conduit tying together the someplace he isn’t to the someplace else he is. Part of me believes my own story might someday be accessed this same way. I can see myself as Liam’s mirrored reflection on the water surface. It’s an image obscured by raindrops and ripples and dimpled from fear and the uncertainty brought on by too many close calls of my own, wondering too if my final breath will be taken as I lay down in water. My last will and testament, to be sure, will be writ along the spine of a split-cane fly rod begging to be held.

This culm of cane I’ve now kept an hour above the fire is tempered. Its resonance, if tapped, has changed from a dull thud to a tight ting. The metals and minerals soaked up through the ground it grew from are forged. No longer pale, the culm is bright and light and seasoned.

Gone is the weight of the water it held until I walk a few steps to the creek and submerge the burnished bamboo completely into the spring. The baptism quenches and cools the cane, infuses it again with cold water. I’ll leave the culm here to soak till morning to balance out an equation, restore what was lost while it hovered in the fire and allow it one last breath from the creek.

Tomorrow I’ll split these fibers with a knife and hand plane them a few thousand times, shaving cane little by little in measured and tapered strips to laminate back together. Down at its end, at the tip, the rod will measure only a few hundredths of an inch across. These few fibers of bamboo will cradle the full pull of a wild fish swimming upstream—an energy that always was will move down a blade of grass and into the bare palm of a hand that holds it in prayer, and into a story.

This bamboo, having become a split-cane fly rod, will never not be. Fire and Water, the world’s oldest gods, become inseparable and indistinguishable, and so is the spirit of a young man who loved what the fly rod reaches for. He carries on along in the seams and lives in the pockets, and he rises and falls in answer to the evening hatch. This fly rod with Liam’s name on it will fly as a phoenix from the ashes along Whatcom Creek and connect to a grab felt first as a subtle tap. The tap will be followed by a force pulling through the grip with a strain in my forearm that moves over the shoulder and comes to rest someplace in my chest.

It is late and I am tired but I am not yet ready to go inside. Through an open window upstairs, the soft and low light of our home spills out to the night like love. I hear the warm acoustics of a Jeffrey Foucault record spinning under the ordinary murmurs of conversation between my wife and our young boys. Their sounds fall onto the back patio and roll over my shoulders before getting lost and found in the chorus of a creek and a fire.

The limitless starlight above me, I know, shines from suns that extinguished a billion years ago. The fire in front of me grew from the embryo of a flint strike and shines its light back to them. So many times I’ve fought a roaring fire that burned the back of my neck and left something or someone lost.

The answerless question When does the darkness end and the light begin? is on my mind, but I lack the mindspace to feel my way around this. It is impossible to grasp the idea that nothing is ever created or destroyed, that everything always was and still is and only changes in shape or form or frequency, traveling on a wave of light and a story that doesn’t end. It rides the crest of Liam’s wave and shines like a sun in every direction. His fire peels apart the dark and burns bright enough to catch the eye of God. Once there was only darkness. Once he swam on the bottom of a freestone creek, under the ink-black smoke of thick hemlock and cedar. In the pocket water, there below the canyon, hatched a billion stars, and Liam resurrected to the surface, out from the shadows, and sipped their sunlight.

As I fall asleep tonight, I hear his story like a lullaby over the white noise and static of a lost creek. Its water is still dripping off my sleeves and lingers like a reprise, perhaps the coda, holding onto the last note of his song.

Jimmy Watts was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest. After finishing college with a B.A. in literature and a few Ironman triathlons under his belt, he read the water for two years as a surf lifeguard in Santa Cruz, California. In the time since, he’s gone on to become a medic and a Seattle firefighter, where he’s assigned to the city’s elite unit, Rescue Co. 1—a special operations team responsible for the highest-risk rescues, including underwater (scuba) rescue. He’s also the craftsman behind Shuksan Rod Company split-cane fly rods, an avid fly fisher, and at work writing his first book. He lives outside Bellingham, Washington, with his wife of twenty years and their two boys.