Autonomy and Purpose in the Mid-Twentieth Century

Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Whatever the vexations or concerns of their personal lives, their thoughts can find paths that lead to inner contentment and to renewed excitement in living . . . . There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides, the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature—the assurance that dawn comes after night, and the spring after the winter.

—Rachel Carson, 1965

The mid-twentieth century was a turbulent time for America’s relationship with the natural world. On televisions that were now customary within the home, families witnessed the horrific realities of World War II, looming tension from the Cold War, and riots in opposition to the civil rights movement. Images of violence resonated throughout the globe and brought into question the nature of humanity itself. Feelings of uncertainty even penetrated daily life. Expansion of the federal highway along with suburban development displaced established neighborhoods and left communities confronting feelings of instability across the nation.

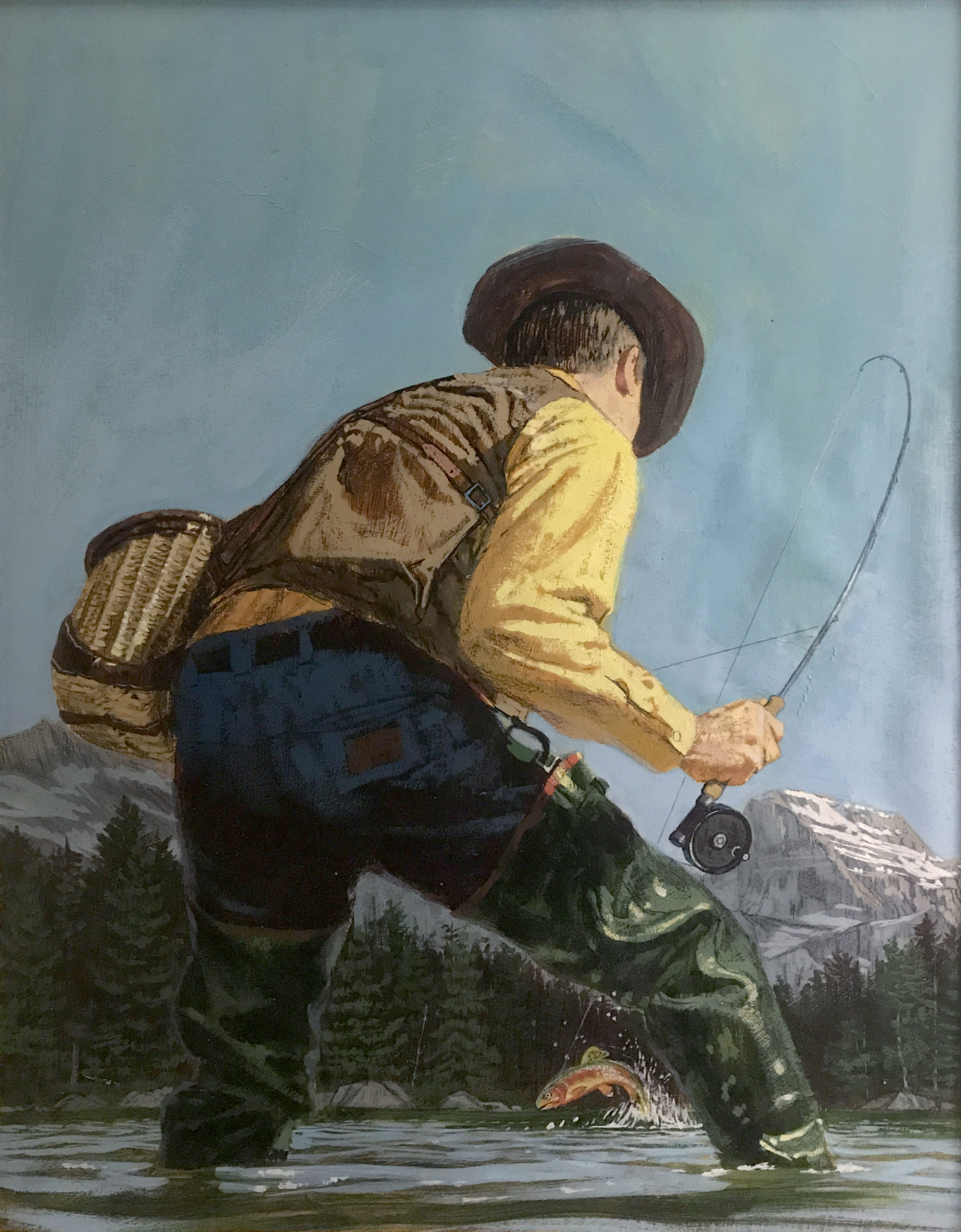

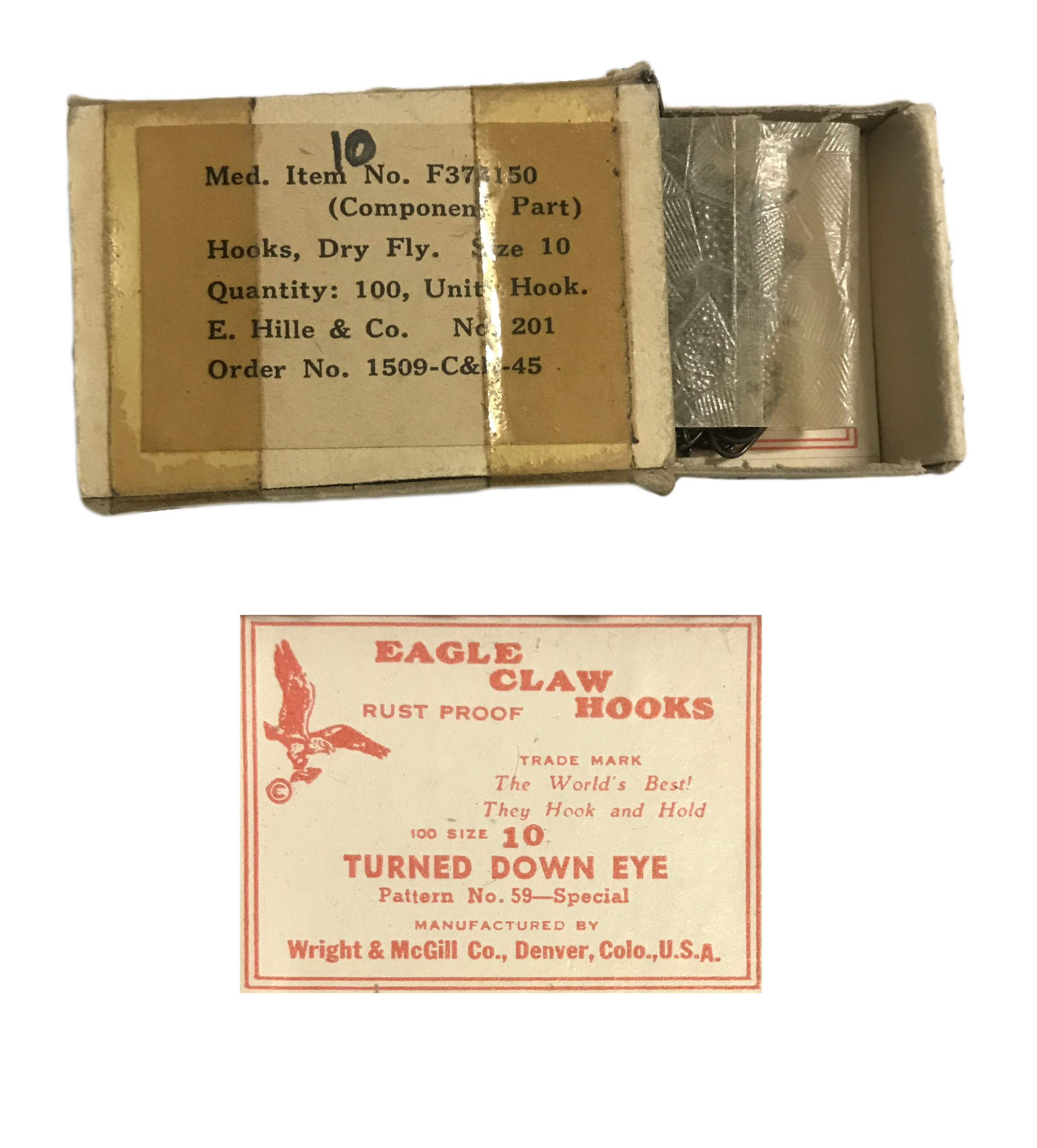

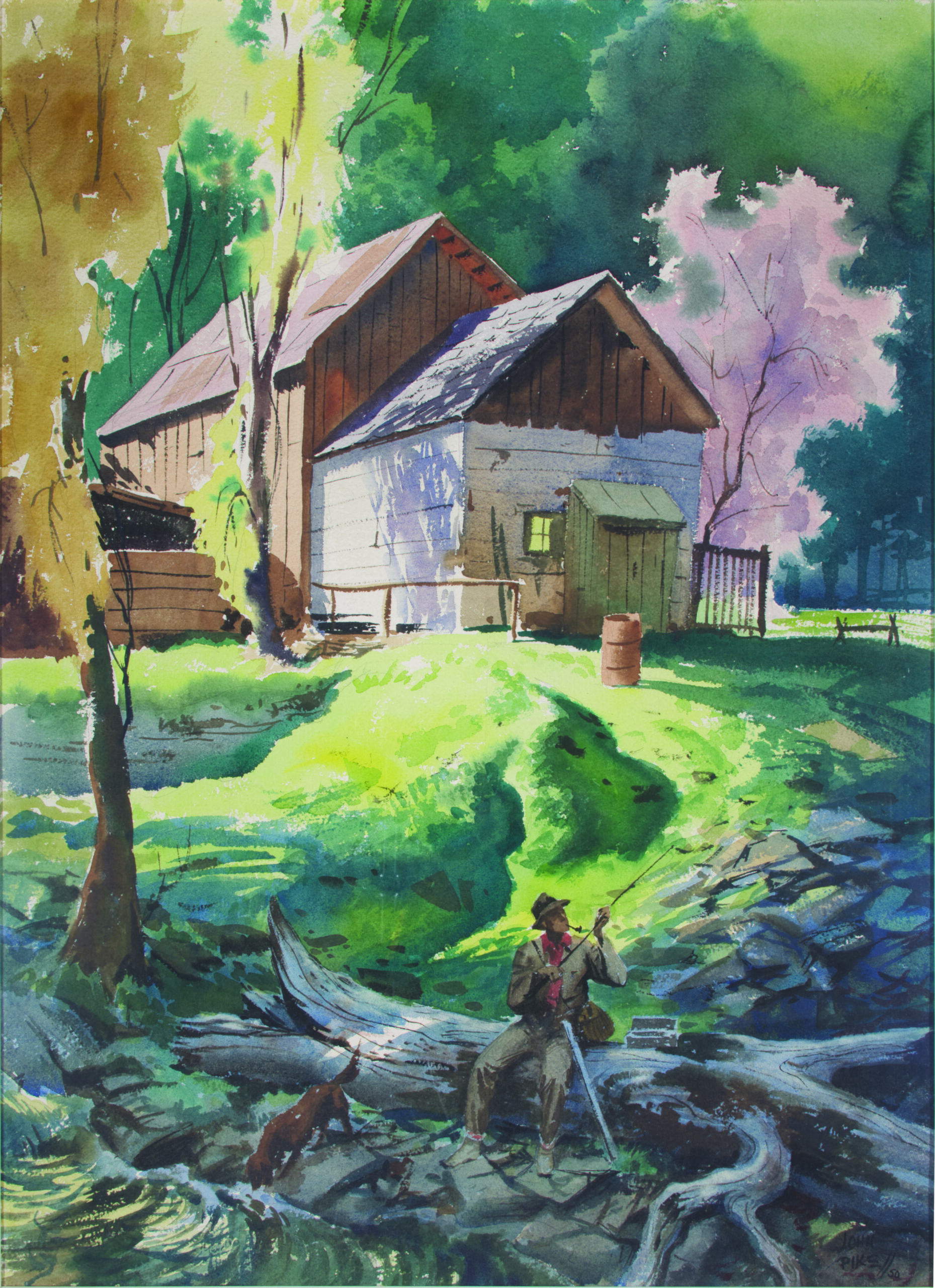

Just as abstract expressionists practiced intuitive movements to channel the emotional tensions of mid-century America, sporting art portrayed the angler in the landscape in action. Instinctual and in sync with the forces of nature, artistic representations of the angler reaffirmed feelings of autonomy and purpose in a chaotic world. Dramatizations of the prepared and capable angler rang true as mid-century innovations in tackle design and material—alongside developments in local entomology—improved success on the water. The angler’s familiarity with the natural world provided reassurance of humanity’s resolve as apprehensive audiences navigated a new frontier.

Taken by Gertrude Jungmann. From her photo album Trout and Salmon Fishing on the Quebec–Labrador Coast, 1953. Gift of Jeaninne Dickey.