“What did you just say?”

Shelby’s question is rhetorical and final. He may not know it yet, but the guy leaning on the boat’s knee brace behind me has just stepped on a land mine. I hope he heard it in her tone or saw her expression after his naïve comment because there will be no more talking between them. If any more words are directed at her, there will be a detonation. It will be ugly, and I am sitting between them. The fly rod goes limp in his hand, and he sits down, sipping beer from his koozie, considering his next move. The only sound now is faint humming from an electric pump up ahead on river right drawing water to irrigate potatoes and the click-click-click of sprinkler heads atop a wheel line. Shelby whips her seat around to face front, toes clenched and bloodless against the bottoms of her sandals jammed hard against the casting deck. She strokes the articulated fly in her hand, smoothing its variegated feathers. She has been dredging the deep channels to tempt brown trout lying in wait, but so far we haven’t boated a fish.

Shelby used similar fly patterns in Alaska and Patagonia. Men within her orbit back then would linger unsure, testosterone-fueled machismo crumbling into awkward smiles, unable to look away as she threw tight loops with a flawless presentation. I can see her laughing at them over her shoulder as she hauls in another slab-sided Chinook or hefty brown trout. big flies for big fish should be tattooed on her forearm. Shelby gazes across the water ahead, remembering those times, no doubt wishing she were there. Images from Yakutat and Balmaceda flash in my head as well, tinted memories from when I too was overwhelmed by her fly-fishing prowess, enveloped by her allure, until the day I said what I felt on a cobbled beach and was left foundering, wondering how something so splendid could collapse into a funeral pyre so quickly. The guy behind me has no way to know, but I’ve stepped on that same land mine.

Up ahead, as the Henry’s Fork slides a lazy turn to the left, there’s wading access to the river. Early August is a good time to spot cars and trucks piled in below Vernon Bridge, and it coincides with inexperienced casters, flailing the water with dry flies, trying to catch fish that will never rise during the heat of the day. There’s just a single rental car covered in road dust pulled over at Seeley’s on river right today. A lone wader stands chest deep stripping a weighted leech just above the weeds. I dip an oar, drift toward the left bank to give him room, and nod as we pass. Shelby turns to me with subversion in her eyes—the bow is swinging toward the Vernon Boat Ramp. She spins back and starts unrigging her rod, nipping the fly off the leader with her teeth and jabbing it on the brim of her cap. The guy behind me hasn’t caught on. The float out to Chester Dam with just him is going to be tricky.

No one ever takes up space in Shelby’s head for long. Many have pretensions to think they might. I tried to keep pace with her but recognized—with my pride laid bare, wondering who she was—that I’d always be lagging and that she’d always dress the truth in her own clothes. Shelby doesn’t chase equality, as some women often feel the need to. Her notable talents are innate and treated the same as her corruptions, with neither one ever suffering a second thought. And she mostly doesn’t mind the company of the rest of us except, like now, when she does. The boat noses onto shore. Shelby hops out and without a word or glance back, she strides away up the boat ramp. The guy watches her go, thinking she is headed for the toilet. “She’s coming back, right?” he finally asks.

“She’ll meet us at the takeout.”

“What’s her deal?”

“You should move up front . . . it’ll be easier for me to show you where to throw.”

Maybe Siddhartha Gautama was referring to guiding when he said, “Life is suffering.” I can see his point; there are manual labors of rowing and obligate good behaviors of assisting and deferring to difficult clients. There are plenty of spiritual labors too because guiding involves a lot of thinking. Perhaps that’s why many fly-fishing guides eventually recognize that clients can be mostly distilled to three categories, which Gautama didn’t comment on since he didn’t spend much time rowing a drift boat.

First, there are clients who strive to be seen. They have not only found the sunshine but struggle to remain in it regardless of cost. Their ambition can inspire others, but as far as I’ve seen, this blind desire more often leaves all sorts of material and emotional wreckage strewn in their wake. When these folks are aware of this, they rationalize the rubble they leave behind is stardust for others to follow. The river and the fish are just another in a long string of shallow and short-lived conquests for them.

Then there are clients who most times remain bogged down with life, suffering in everyday metaphorical shade. Ordinary folks, who come to not only recognize the light they rarely touch, but the circumstances that keep them from it. For them, the river and fishing are maintenance for soul and sanity, though they may not be conscious of it. The fly rod becomes their connection to a peace that subdues the numerous thoughts in their head competing for attention. For these folks, you really try to make a great day of it. The river and the boat reduce the complexities of their world to a singular consideration for the next few hours. They never know it, but this watery construction is often as much of a restorative for the guide as it is for the client, their fish and their triumphs many times lingering as much in my memory as theirs. People ask, “Why do you guide?” Because every time my boat slides into the water, hope floats forever promisingly along with it.

Finally, there are a very rare few who recognize that all things end well if you believe it so. With these folks, the most sought-after and most sincere qualities of human nature arise. Gautama aspired to teach us to be these people—they have let go of suffering. The river and the fish are one continual path: any outcome, every outcome, ends in happiness. In my case, there’s got to be more to it than just racking up good river karma because so far, despite my best meditations with the sun beating down and wishing I could someday get a day off, I’ve never managed to float away to nirvana.

There are two ways things could go as far as my tip is concerned. I’m tending to place the guy, now moving clumsily to the front of the boat, in the first category: a player who hopped a plane from L.A. up here for the week. Without any of his acolytes around to demonstrate his liberality to, my tip will be meager, especially with Shelby stomping off. On the other hand, he may just hand over his primo fishing outfit when we get to Chester Dam. This happens more often than you’d think. Over the seasons, I have collected rods and reels that were used once or so and given over as a final gesture from well-financed clients certain they would never return.

This guy had somehow chatted up Shelby in the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar in Jackson and had fished down from Yellowstone Lake to Alpine in Shelby’s boat on a personal gig. Why she decided to bring him over to the Henry’s Fork instead of continuing down the South Fork in her own boat is beyond me. She knows the South Fork as well as I do, and it’s fishing better right now. The yellow Sallies are still coming off well. The Henry’s Fork is always tough this time of year. Water temps drive the fish deep, and clients don’t want excuses about biological oxygen demand or trout physiology. You’re supposed to be the one with the cheat codes for catching fish, no matter the hour of day or season. “Just get it done before it’s time for gin and tonics, okay?” You tie on a brown rubber legs and troll it behind the boat hoping a whitefish will suck it up and save your ass.

I slide the boat off the ramp back into the current. The guy, now in front, remains motionless, fly rod across his thighs. Just as I start to say something, he steps out of whatever mental debris he’s been tangled in. He stands up and begins casting, going deep and stripping in earnest. His casts are mindful and directed. This isn’t his first weekend on the water after all, and I decide I’m going to boat a fish for this guy if it takes all day. Unfortunately, the places between here and Chester Dam that offer any reasonable chance in the afternoon are slim. The weedy glides and deep channels holding most of the fish are behind us. There is a basalt wall, though, that gradually curves out into the current downstream aways on river left. Water pillows up in its throat and leaves an outer edge that forms a subtle eddy fence that swirls away downstream. It’s a well-known river feature, and newbies always fish the throat where the water piles up and scours a deep hole. Big fish do sometimes hang out there, and if you were to believe the fishing lore on the internet, it should be the place to cast your fly. I have learned there are alternatives.

To those who listen, Gautama would have whispered a koan, “Where are the fish besides where you expect?” If you focus, you’ll find enlightenment in a lovely scum line. There are indeed big fish in the deep hole, but there are hungry fish, lower in the feeding hierarchy, down the bank side of the eddy fence where the water slows and food items tumble out of the recirculating current. That thin meandering line of foamy debris is a handy surface marker to visualize the eddy fence and an answer to Gautama’s paradox. I scull downstream of the hole and anchor up, telling the guy to move to the stern and cast back upstream inside the foam line. He does okay, but he’s getting tired and sloppy. This all changes after a few casts when his line zings to life, nearly jerking the rod from his hand. We boat a fine rainbow I measure at 16 inches and then another from the same spot at least 2 inches longer. He fishes on with renewed energy, but to no avail. Midafternoon on the Henry’s Fork in late summer is more than a challenge for anyone. Even so, he has succeeded with a two-fish release, and his contentment will not be denied.

We continue downstream to Chester Dam. Shelby is not at the takeout; neither is her pickup. I offer to drive the guy to Alpine even though it’s way past the fly shop at Palisades. He waves me off, says he’s traveling with buddies who are in Ashton and will come pick him up. He chats with them on his phone, texting pictures of his fish. He tips me three crisp Benjamins from his wallet and even helps me trailer the boat. He genuinely thanks me and genuinely smiles. I leave him leaning against a picnic table laughing as his friends arrive. Grand Teton glows coral pink as I head south on Highway 20 toward St. Anthony, and I’m left a bit undecided which category to place this guy in.

Back at Palisades, I park the rig at the fly shop, empty the ice chest, and stow my gear for tomorrow. I transfer Shelby’s rod and boat box into the back of her pickup and walk across the highway. She is there, sitting beside Larry, helping him with receipts. Larry, our outfitter and confirmed Luddite, considers computers with disdain, preferring expenses written in a ledger and sums totaled by hand. Shelby uses the calculator on her cell phone to check his work. The rest of our crew slouch in the yellow glow of the Pioneer Bar and Grill’s varnished log interior watching Mariners baseball on the TV above the bar. There are two nonfishing tourists near the door finishing hamburgers.

Larry asks me to take a newlywed couple through the canyon stretch on the South Fork tomorrow. They are in Jackson tonight, driving here in the morning. Larry feigns an apology. He knows this translates to a late start from the Conant Boat Ramp and a long push on the oars out of the canyon to Byington in the afternoon when the upriver wind notoriously picks up and rushes back toward the Continental Divide. It’ll be a fight with a boat that wants to weathervane and fly lines in novice hands that whip precariously out of control. Larry knows I’m okay with it—the canyon is beautiful. There are no electric pumps or wheel lines there. It’s filled with splendid old cottonwood galleries and sun-dappled runs of cool water. What’s more, there are loads of whitefish in the canyon too, and if all else fails, trolling a brown rubber legs will almost always bring them to the boat.

Shelby will take a couple businessmen on a milk run from Palisades Dam down to the highway bridge on the South Fork. They’ll miss most of the action, which is happening in the braided channels just above Conant. I don’t think they really care. Larry will pick them up at the bridge and drop them off for dinner at the South Fork Lodge. The selection of single malts there is much better than the Pioneer has to offer, and you can watch late floaters loading out at Conant with your feet propped next to the outdoor fire pit. The businessmen are repeats from Atlanta. Clients who have fallen under Shelby’s persuasive powers quickly find there’s no remedy. They always ask for her.

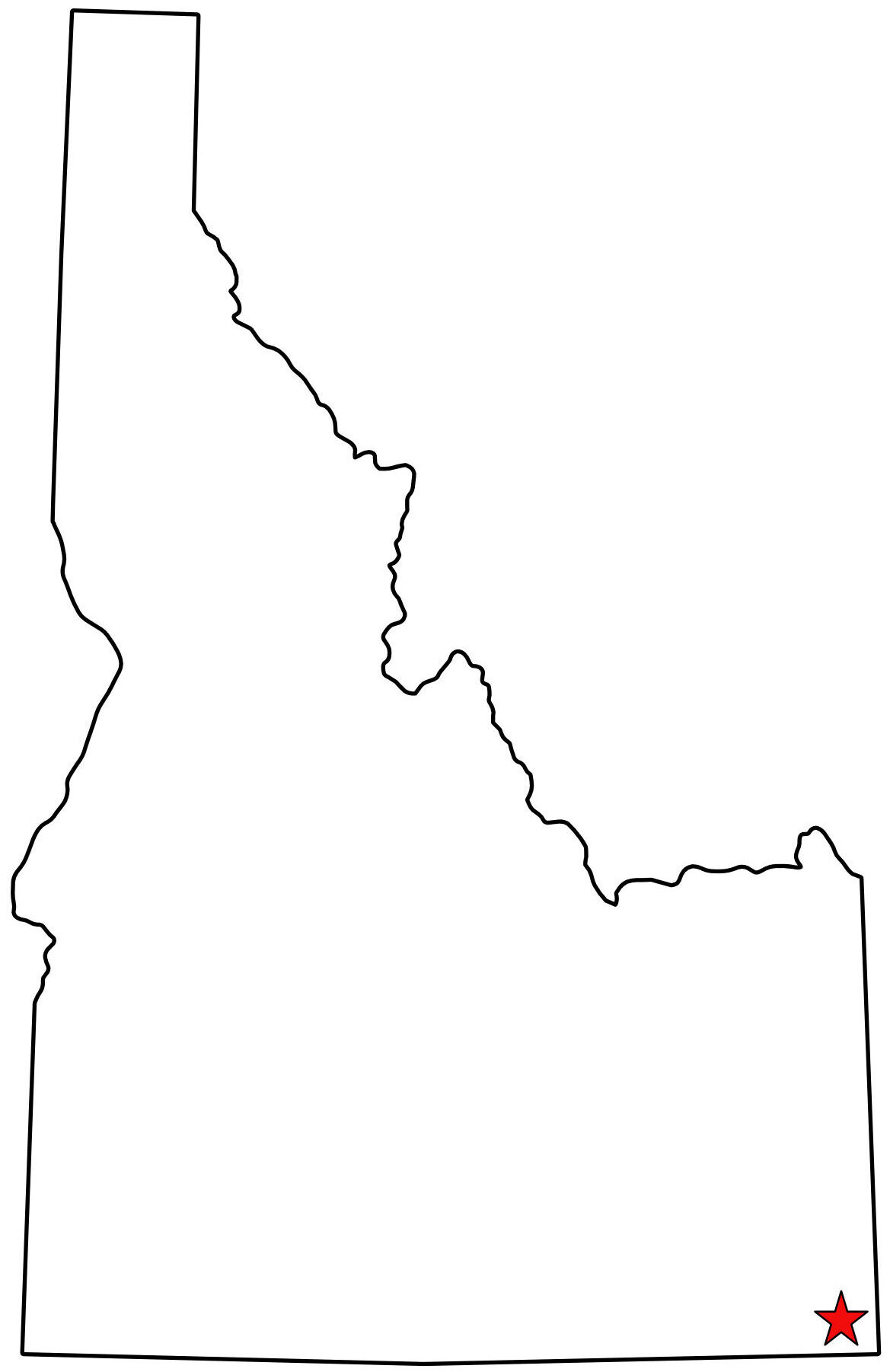

It usually begins with the large outline of Idaho concealed and tilting eastward on Shelby’s left side. Several whitewater and fly-fishing guides have similar tattoos. It’s a tribal thing to Idaho natives, a subtle discrimination to out-of-state guides. The southwest corner points toward her navel while the northern panhandle traces up past the bottom of her ribs. The southern border angles sharply down and around behind her hip. Most importantly, a tiny red star indicates her hometown in the southeast corner of the state. In Shelby’s case, her choice of the tattoo’s location is what I think the military refers to as a “force multiplier” because she deploys it to complement other assets. “Where are you from?” is the innocent question put to Shelby by an unsuspecting male client that triggers her streamside shock and awe. An uncomfortably long pause follows as she considers the best way to explain. Then as if giving in, she’ll pull her shirt up exposing the bottom of her bra, hook her thumb in the waist band of her shorts tugging everything downward like a Coppertone ad to reveal the entire state, and nod to the star well below her tan line. The question is answered without a word, and suddenly everyone begins to fidget and feel hot in the shade. I’m sure the guy from L.A. is amusing his buddies in Ashton with the story of meeting an Idaho fly-fishing guide from Montpelier with a well-placed, red star on her backside.

One of our new guys manages to forget his popcorn in the microwave. Blue smoke churns across the Pioneer’s ceiling. Larry is yelling, the smoke detector is screeching, and I head outside and across the highway toward the fly shop. Shelby slips out behind me. She jogs over and loops her arm through mine and says she’s been meaning to ask if I would go back to Chile with her this fall. She’s taken a job guiding out of Coyhaique for their summer season. Aspen leaves applaud in the evening breeze. Her chin presses softly on my shoulder. A barely audible South Fork slides along nearby. Her closeness begins a delicate reordering of my memory, rendering past recollections imperfect. From the rowing seat, I remain convinced that I’ve somehow been allotted more grace in life than most but, I must concede, Gautama was right. Life is suffering.

Matt Powell’s writing centers on his lifelong interests afield, which have taken him to many corners of the world. His hunting and fishing stories and his bird dogs have been featured in outdoor magazines and on television. Matt is a professor at the University of Idaho, where he has studied trout and salmon for more than twenty-five years. He lives in Southern Idaho with his wife and their two Weimaraners.