by George Rogers

Gilles McLean* smokes Chelseas. He buys his cigarettes at the Pick n Pay in Mutare—a two-hour drive on the A14 from where he lives in the Nyanga Mountains—for just $1.55 a pack. Like most Zimbabweans, he pays in American dollars instead of his country’s own spooked currency, shielding himself from this month’s 77 percent rise in inflation. So his cigarettes are still a bargain, but it will soon become obvious to us—my wife, Denise, who sits directly behind Gilles now; Witt, my college-bound son who’s keen to do some African fly fishing; and me—that they are killing him.

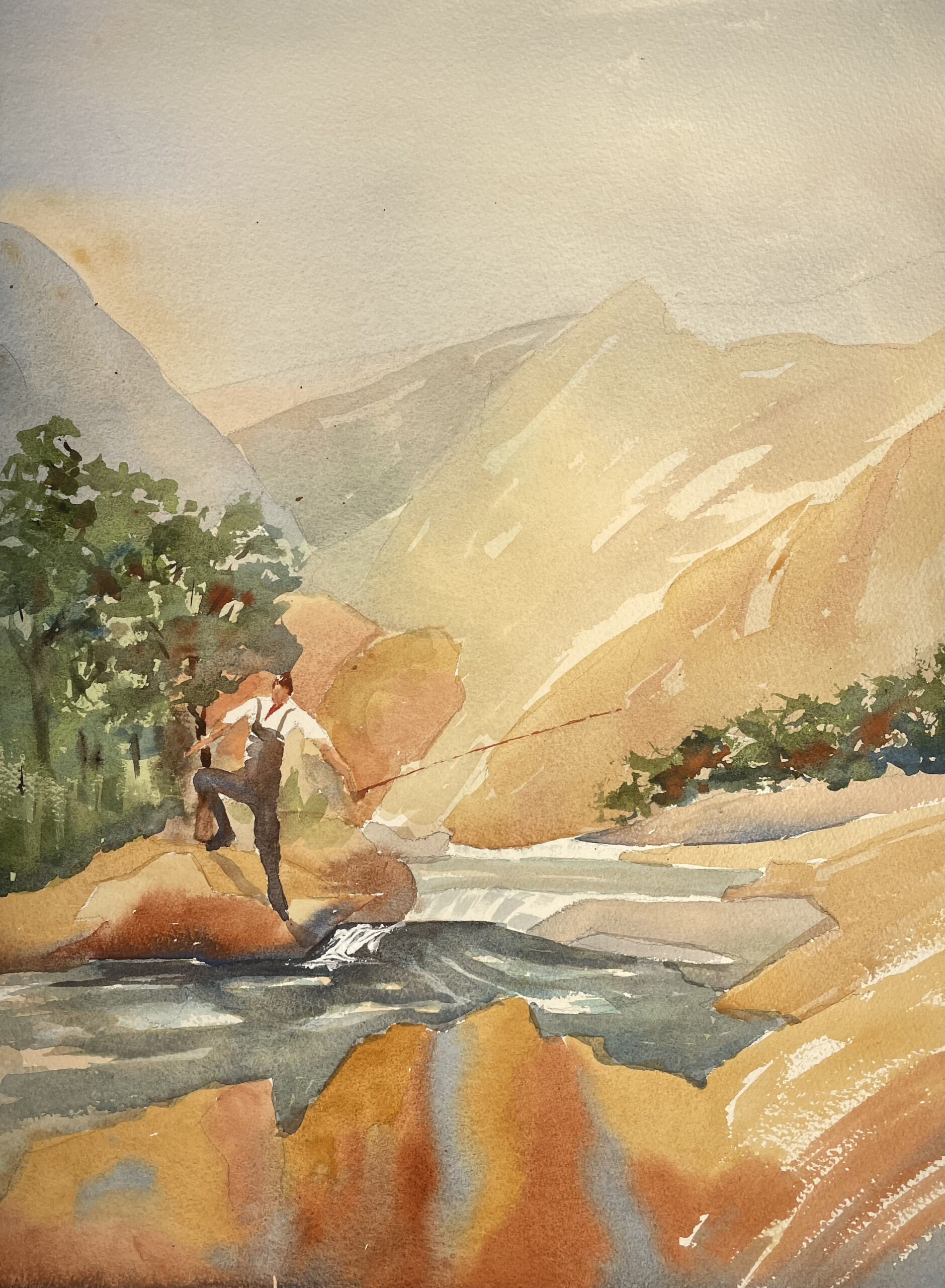

Gilles smokes as he drives, cigarette held thoughtfully out the cracked window of his Land Cruiser, flicking ash as we bounce deeper into Nyanga National Park, much of his smoke curling back in again through the rear passenger window. My son muffles a cough and Denise rolls up her window. Gilles is our guide for the day and we’re headed into the park, hammering down red laterite roads, hugging the contours of hills dotted with ancient pit formations from the Ziwa people, a landscape of dolerite and sandstone, just kilometers from the Mozambique border, where we will be fishing the Upper Gairezi River for what Gilles tells us are feral trout: trout he assures us are still there.

This may be—at its core—just a fishing story, but it’s also a story about Gilles and Zimbabwe, and the slow disappearance of brown trout and colonialism from a country long regarded by much of the world as politically incorrigible. It’s the story of one man’s loss: his land, his trout, his health. Improbably, it’s also a story about the giant mottled eel—a species, I should note, about which Gilles has nothing good to say.

Vestiges of colonialism, the trout that we’re after today have been in these freestone mountain streams since Gilles’s grandfather helped introduce them to the Eastern Highlands: Loch Leven–strain browns that spread through the web of rivers in what was then Rhodesia, left like Marmite, toast, and tea in the wake of an expanding British empire.

Brown trout are little stones in the flour, hanging on where they can, difficult to shake free once established. They are survivors. Here in Zimbabwe they’re also, let’s face it, invasives, although few people—especially anglers like Gilles—would ever think to disparage them with that word. But these trout settled in and, like the English, made much of Southern Africa their own, not necessarily welcomed by the native fish they displaced—endemic species of yellowfish and catfish mainly (Hilda’s grunter, the Pungwe chiselmouth, the Gorongosa kneria, the giant mottled eel)—but tolerated, maybe, in the same way that Zimbabweans initially tolerated the English.

Descending into the Gairezi Valley, Gilles’s Land Cruiser labors marvelously along, dropping below the fog, allowing us to see—for the first time this morning—the ribbon of water we will be fishing. Gilles eases his rig over a crossing of the Nyama River, what he calls a causeway, although it seems as if we’re just lurching over a conveniently shallow boulder garden that today is flowing not quite tire high. Gilles takes it slowly, and after climbing up and out of the Nyama, we’re on our way, passing tracked logging trucks that, shockingly, operate in Nyanga, one of the country’s oldest national parks. They’ve punched new roads into the river bottom, looking to haul out the gum trees and big pines, and I can tell that, to Gilles, the place is now unrecognizable.

We pull over and Gilles steps out. He takes a look at what he thought he knew. He’d wanted to take us here because it’s one of the last stretches of river in the country with wild trout, 18 kilometers of water still controlled by the Nyanga Downs Fishing Club that his grandfather had belonged to. But now all this: silt and slash and log landings. He climbs back in and lights another Chelsea and we bounce down the road some more, passing a log lorry that’s slid off the road, this one abandoned, its front wheels—although they are 5 feet high—claimed by the ditch. We parallel the river and stop again, this time where we’ll start fishing, while Gilles wonders aloud how to get his Toyota safely off a logging road with no shoulders.

“They stock these rivers with a helicopter,” he tells us. “That way you don’t have to drive back here,” he says. “Which would be crazy.”

“You mean like we just did?” I say as he backs his rig into the brush, maybe far enough off the road now to avoid a fishtailing trailer of logs.

“Exactly,” says Gilles.

Gilles wears a bucket hat and a green sweater, river sandals, and brown dungarees with holes in the knees. He’s a man who’s spent his life outside, farming and fishing under the African sun, and his face has the rough and rusty precancerous patches above his eyes and about his temples to prove it.

We string our rods and Gilles offers us a local favorite—Clark’s Killer—a pattern I’ve never seen that resembles a small freshwater crab. The fly, tied on a size 12 hook, drab brown and about the diameter of a typical shirt button, resembles the small crabs found in the Upper Gairezi River, a species only recently described by science as the Mutare River crab, but a crab that anglers have obviously, based on this matching fly, known for years.

The Gairezi, full of pocket water and punctuated by deep pools, is as clear as new glass, but as we fish we see nothing more than bushbuck tracks and—on one sandbar—the prints of a Cape clawless otter. There are also the carapaces of the little Mutare crabs scattered here and there, on the tops of boulders mainly, having fed something—birds or otters, it wasn’t clear. We all fish: Denise and Witt, myself, and Gilles, working this beat, hopeful in the way that everyone begins the day. Gilles fishes behind us, swinging his crab through the big pools, telling us his best fish here was a 6-pounder—but by midmorning, we haven’t moved a trout.

“We still have a man trapping eels,” Gilles tells us, gesturing downstream.

“Have you seen them?” my son wants to know.

“Once. Down in the rocks. Moving like a thick black tongue.”

“Does he catch many?” I ask.

“I don’t know how hard he traps anymore,” says Gilles. “That’s part of the problem. He’s an old man now. The other problem is these damned roads.”

“But your eel trapper,” I say. “Why does he do it?”

“Well, we pay him. And he gets the eels,” says Gilles. “There aren’t many like him anymore, men with the traditional traps.”

“Could he have fished here? On this river?” I ask.

“He didn’t fish with a rod,” Gilles says.

“But if he had wanted to fish with a rod?”

“He never asked,” says Gilles. “But I take your point. The club was exclusive for years.”

“That’s a way of putting it,” I say.

“Listen, we ruled for too long,” Gilles says. “And we didn’t let go of this country ’til we had to.”

The giant mottled eel—Anguilla marmorata—is a muscular eel, growing to more than 6 feet and weighing up to 45 pounds. It’s a tropical, freshwater eel, a deeply marbled, yellow-greenish-to-black animal that can live forty years and migrate hundreds of miles across the Indian Ocean to where it’s thought to breed west of Guam. They’re carnivores. Nocturnal. Eating crabs, frogs, fish. Gilles will tell you that they target trout. They may, although based on what’s known about these eels, they seem to prefer—like the trout—crustaceans, specifically the Mutare River crab. But what is true is that these eels have always been here. They’re the locals. There’s no doubt they belong; they are the native fish, the endemics that despite years of trapping are still there: quiet in the bottoms of the deep pools, nosing through roots and rocks in the shade of the big trees still standing.

The morning that Gilles lost his farm was no different than any other morning in Africa, what with the doves calling and the heat of the day slowly waking the cicadas. It was a normal morning in every way except for the men gathered at his gates, holding hoes and shovels and adzes. Tools, yes, but with the men holding them like that, so casually, over their shoulders—men who would soon drive out Gilles’s laborers and family—it was clear that these were not farmers and that what they carried were not intended to be used as tools, but as a reminder to Gilles that other white farmers had already been killed and that they had the blessing of Robert Mugabe, their president.

When men gather and glare at one another, it’s often only the merest slight—a look, a remark—that provokes an eruption of violence, and it’s in the choreography of these moments that the hate starts to gather. It does not take much to kill a man. A hammer blow or a dozen good stones. The back of a cold shovel. Men kill in batches when they catch the scent of the crowd, their compassion forgotten as, together, they lift the first stones. And it doesn’t take much to make the first man go down. After that, the others—crouching, usually speechless, not begging for their lives like in the movies, but more often in shock or stumbling numbly away—begin to look less like men and more like animals, and that’s when the worst of it comes down on them like hail and fists.

Gilles’s farm in the Karoi District, 3,000 acres in north central Zimbabwe, had been passed down—like the right to fish the rivers of the Eastern Highlands—through his family. He knew at one time this land had not been British and that intellectually, at least, he could understand the urge for Mugabe’s cronies to seize land that, years ago, had ostensibly been taken from their grandfathers. Maybe he could even see that this land had never really been his, but the hundreds of cattle he owned and bred certainly were, as were his tractors, barns, and home. Those were certainly his—and this is what he may have been thinking as the first stones went through his windows.

“Did you think to fight back?” my wife asks.

“There was no fighting back,” says Gilles.

It’s a question of who belongs. What fish? What people? Whose land? What stories are true and which are simply told? What story would the eel trapper tell? Would he tell of a time before men owned rivers? Before anyone had thought to claim water? Would he tell a story of a time when rivers were wild and bursting with eels? A story, I suspect, that would not be a story of trout, but a story of a river that never knew trout: a time when rivers, swollen with rain, spilled from their banks, and eels, on full-moon nights, swam through these forests, glistening.

Back at the Land Cruiser, Gilles pulls out a wicker basket and a folding hardwood table, even a tablecloth, spreading it with a flourish as we watch it settle over this unexpected little luxury. Gilles says that since there’s no place to picnic properly, the roadside will have to do, and the lorries can wait for us or squeeze by. It was an English lunch that we could not—as Americans—have imagined, what Gilles called a proper lunch: a salad with beefsteak tomatoes and lettuce picked that morning, with croutons, balsamic dressing, and real cutlery. For drinks, there were choices: a South African zinfandel, cold Bohlinger’s lagers, or tall Cokes in real glass bottles. As a snack, Gilles served honey-drizzled peanuts home roasted the night before and, for a main course, hot dogs stuffed cleverly into a large thermos that kept them surprisingly warm and a tin of biscuits for dessert.

While we eat, Gilles talks. He tells us about the farm invasions and Mugabe’s kleptocracy, raging hyperinflation, food shortages and rolling electrical blackouts, international sanctions, and—gesturing around to what we’ve seen today—clear-cuts in national parks and no trout. The world Gilles once knew is gone: his farm and livelihood, his home and land, and probably, it seems to me, his trout, but also the colonial past and its attending privilege. Yet it’s also obvious in listening to Gilles that even after everything he’s lost, and the country’s largely self-inflicted wounds, this is still his country. He’s a Zimbabwean at heart.

After lunch, we fish upstream. The water is clear and low, and we cast with no expectations now, the day bright and hot, and it’s good to be walking through cool water. I work ahead and Denise begins to pay more attention to the birds and the flowers, while Witt climbs the biggest boulders he can find, looking for trout in their shadows. On the banks, caught in spiderwebs, are insects I’d never seen, and we fish without speaking, leap-frogging each other, with Gilles still working behind us, although he’s coughing more now: a hoarse, dry cough that comes over him in spasms, leaving him bent and breathless as, now and again, trucks sway by, heavy with logs.

Later that afternoon, Gilles says he wants to try one last spot, and he’s no more than said so, it seems, then we’re back in his rig, banging back down this road once again in Gilles’s green Toyota. He parks above the river, high enough that we can only see distant flashes of water below, and soon we’re walking toward it. The walking is hard, although it’s downhill and with the river in the distance, flashing blue through the trees, we keep on, encouraged. The loggers have cut everything here—every tree cut and limbed and bucked to length—yet we bull through the mess, through the slash and pine tops left in the wake of the hydraulic harvesters. Gilles soon falls behind, but he waves us on. Tells us to go ahead. From where we stand now Gilles looks smaller and older than he has looked all day. Near the river, the hills are steep and still forested, the loggers unable to reach these ridges. My son pushes upstream still hoping for an African trout, but Denise and I wait for Gilles. In time he crests this last ridge and joins us, and together we sit bankside, the three of us, watching the water in the shade of these big trees, thinking that this is how it must have always looked, and that—from here at least—you might believe these trees go on forever.

On the side of the road on our last morning in Zimbabwe, out walking, not long after fishing with Gilles, I came across three men struggling with a stout branch of maybe 10 feet as they worked to position it and a sizable stone under the frame of their minivan. It was a van with no door, and, I soon realized, a van with no jack. Yet they worked the limb into place and seesawed the Honda high enough (after digging a bit) to slip off the flat and send it on to be patched, one of the three rolling it back toward town as the others settled in to wait. I asked if they needed help and they thanked me and said that help, in time, would come. And by the way, they wanted to know, what did I think of their boat?

I’d seen the boat strapped to their roof but decided not to ask about it due to its condition. I’d assumed the boat was a tragic story: a forty-year-old fiberglass hull, maybe 14 feet long, an old boat, heavily used—so heavily used that the entire bottom was missing, by the looks of it torn off in some catastrophic event. My first thought was that they’d bought it after the previous owner had drowned. But that wasn’t it at all. Instead, they smiled hard and told me of their good fortune in finding it washed up. They told me of their plans for it, and I listened without skepticism, assuming that men who change tires with tree limbs can also work miracles on bottomless boats.

This is Zimbabwe. It’s a boat with no bottom. A van with a flat and no jack. A country propped up on three wheels, thinking only of its good fortune, like the luck of finding a boat—even one with a giant hole—and imagining it patched and floating, skimming someday, however improbably, over the waves. Zimbabweans, I realized, have had so little for so long that having anything now seems like the start of something.

Tonight the moon rises, heavy and low, and maybe the big eels will decide that it’s finally time. After as many as twenty years in these streams, eating the little Mutare crabs and dodging the eel trapper, it might be: time to begin the trip to the sea, leaving the headwaters in the Nyanga Mountains and winding downstream through the Gairezi and its private beats and stocked rainbows, past the woven traps and dams and the Mozambique border, then north to the Luenha River and on to the big Zambezi, flowing 120 miles more, south and east, across the heart of Mozambique, to the port at Chinde town, where most, but not all the big eels will dodge the gill nets and handlines set drifting before them as they push across the Mozambique Channel, filled with purpose and moving in the way that all creatures move when gripped by the urge to spawn—the big females ripening, heavy with eggs, guided somehow back to where they’ve always gathered, wherever that may be—dutifully returning themselves to the ocean where their eggs will drift to the rhythm of the moon, at the mercy of its orbit and the sweep of the sea.

*Because Zimbabwe, according to Amnesty International, represses freedom of expression and dissent, this is not his real name.

George Rogers is a high school science and English teacher who lives in Chateaugay, New York, with his wife, Denise. He spends summers at his cabin in Cantwell, Alaska, where he owns and operates Denali Angler, a fly-fishing guide service.

Rogers’s work has appeared in numerous publications, including the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times. He is currently a senior contributor at the Drake magazine. His “The Last Good Days of a Very Good Dog” topped the Boston Globe’s 2022 Top 10 Ideas essay list, and “The Pink Ranchers” was named a notable essay in The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2023.