By G. William Fowler

The American Museum of Fly Fishing has a permanent collection of more than 22,000 artificial flies. This is the story of five of those flies, which were recently donated to the museum. It is coincidentally the story of the beginning of a friendship between two prominent American anglers: Art Flick from the Catskill Mountains of New York, the tier of the flies, and John D. Voelker from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, who received them.

Flick and Voelker were known as small-town country sportsmen who abhorred big-city life and shunned the limelight. And yet, history has rightfully made them giants in the sport of American fly fishing. John D. Voelker (1903–1991) was a lawyer, prosecutor, Michigan Supreme Court justice, and prolific writer. Among his eleven books—published under the pen name Robert Traver—were Anatomy of a Murder, Trout Madness, Anatomy of a Fisherman, and Trout Magic. Arthur B. Flick (1904–1985) was an accomplished fishing and hunting guide, longtime Westkill Tavern innkeeper, fly tier, fly innovator, conservationist, and the reluctant writer of Art Flick’s Streamside Guide to Naturals and Their Imitations, a significant entomology reference book described by Ernest Schwiebert as “essential in the working library of any fly-fisherman.”1 Because of Flick and Voelker’s prominence in the sport of fly fishing, these five flies have a unique place in the history of how Flick’s artificial fly patterns migrated from the Catskills to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

The provenance of these particular Flick flies began in 1961 when Voelker wrote what he called his first fan letter.2 “I have fly-fished for trout for over twenty-five years and never before really felt I had penetrated the mysteries of this nymph-dun-spinner cycle or had the nymph-dun correlation explained to me with such exciting simplicity until I read your Streamside Guide, which a friend just sent me.”3 Voelker also sought the name of a good fly tier to replicate Flick’s patterns.

Flick responded to Voelker’s letter, saying that Voelker might consider contacting Harry Darbee, of Livingston Manor, New York, “but [he] is so busy. I doubt if he would even answer your letter, although you might give him a try.”4 Voelker responded with a cordial thank you, saying that he had purchased extra copies of Flick’s Streamside Guide to give to two of his favorite local fly tiers. “I am hopeful that at least one of them ‘catch fire’ and tie them as exactly as you describe.”5 As a token of appreciation, Voelker included a copy of his book Trout Madness and invited Flick to come to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to fish. “If you ever get out here I can put you over some nice native brook trout. But you’re probably like me—I’m invited lots of places to fish but prefer to stay home.”6

When Flick received Trout Madness, he realized that Voelker and Robert Traver were the same person. Flick was embarrassed that he did not immediately make the connection and responded to Voelker, confessing to a “terribly red face.”7 In response, Flick enclosed a piece of pink-tone fox fur and commented that his Hendrickson was not a standard version because he used “a more ‘pinkish’ body. This will probably make up more Hendricksons than you will use in your life, but that touch of color does seem to make a difference.”8 Flick then sent Voelker ten flies of his patterns.9 Voelker felt an immediate kinship and replied with another letter, again inviting Flick to come to Michigan.

I too hope we can fish together some day. We have miles of trout water that are scarcely touched. The tourists won’t get off the main highways, of course, and the real fishermen who pass through here are high-tailing for Canada. If you can get up here I can sleep you and feed you and put you over some pretty nice trout on lovely trout waters. All I do is fish all summer so if you can make it come any time, just warning me so I’ll be on hand to meet you. On second thought, my daughter Julie is getting married on July 8th so that day is out as my wife tells me she thinks I’d better be on hand for the occasion. Aren’t women funny?10

More letters were exchanged, with Voelker continuing to promote the good fishing and Flick always graciously declining; but Flick was encouraged by the sincerity of the invitations and decided to make a week’s trip to fish with Voelker in the summer of 1962.

The full story of Flick’s travels to the Upper Peninsula and his first meeting with Voelker is recounted by Voelker in “A Flick of the Favorite Fly” (a chapter in Trout Magic), an upbeat, humorous, and exaggerated, but mostly truthful, story.11 The details of Flick’s trip to the U.P. can also be found in Voelker’s “Fishing Notes.” Flick arrived on 29 June 1962. Life magazine photographer Robert W. Kelley and Voelker had been fishing for a couple of days and working on the photographic layout for their new book, Anatomy of a Fisherman.12 Flick and Voelker fished together for six days, with Voelker catching eight brook trout and Flick catching ten.13 The sizes of fish are not specified, but Voelker’s notation “F” reveals Voelker caught five fryers and Flick caught only one. (The term fryer refers to smaller trout that might find themselves in a frying pan.) The fishing did not live up to Voelker’s expectations and caused him to record in “Fishing Notes” on 1 July 1962, “As Pierre the guide said, ‘You should have been here next week.’”14 William E. Nault (1912–2001), a well-regarded fly tier from Ishpeming, Michigan, joined Flick and Voelker on the afternoon of 2 July 1962 on the Hoist River. He did not catch a fish, but Flick caught four and Voelker caught one.15 Bill Nault, a chemist and outdoor writer, turned out to be the tier to “catch fire” about copying Flick’s patterns. He too wrote about the day he fished with Flick and Voelker.16

Provenance

Voelker eventually gave his ten Flick flies to Nault “to insure that Nault tied up exact duplications of the flies” described in Streamside Guide.17 Nault preserved all ten of the flies for thirty-five years. In 1996, at age eighty-four, Nault was in a nursing home and—fully aware of the historical significance of the flies Flick gave to Voelker—decided to donate the ten flies and a verification letter explaining their history to the Fred Warra Chapter of Trout Unlimited for the annual dinner and fund-raising auction. Mike Stefanac and Mike Anderegg of Marquette, Michigan, joined together and were high bidder. They divided the flies by drawing lots. Stefanac chose a Grey Fox, Grey Fox Variant (small), March Brown, Hendrickson, and Stone Fly Creeper. Anderegg kept a Cream Variant, Dun Variant, Red Quill, Early Brown Stone, and Hendrickson Nymph.18 In 2015, Stefanac sold his five flies and the verification statement to the author with the knowledge that they would be donated to the American Museum of Fly Fishing in 2016. Anderegg still has his five flies and the original mailing box with a Westkill Tavern shipping label.

The craftsmanship of Flick’s creations are well-done, “precise sparsely dressed flies.”19 The workmanship is “so perfectly executed, that once you became familiar with Art Flick’s work, you could pick his fly out of a thousand.”20 A characteristic of a Flick fly was his use of “ultra stiff glossy dun hackles” from gamecocks he personally raised.21 When high-quality English capes became unavailable in 1933, Willis “Chip” Stauffer, an engineer for Mercoid Corporation in Philadelphia, helped Flick get started in raising gamecocks from eggs acquired in England to ensure the highest-quality hackles.22

Flick is credited with popularizing the Variant style of dry fly.23 Dick Talleur describes the Variant style as “a true high-rider. It employs an oversized hackle: two, three, even four sizes the normal. There are no wings; the upright, prominent hackle fibers comprise a rough wing silhouette. The tails are longer than normal, in order to balance the oversized hackle. The body is small, almost inconspicuous; often a quill of some sort. . . . Variants are dancers; saucy ballerinas performing tiny arabesques and pirouettes on shimmering riffles and glides.”24 No wonder Talleur is captivated by the Variant.

Part of Flick’s genius was to advocate the use of a limited number of fly patterns, instead of hundreds of variations, to successfully fish any Catskill river for brown trout. Without wanting to offend the commercial fly tiers of the era, who were offering countless patterns, Flick proposed ten patterns, concluding “Experience has convinced me that a good imitation of any of the materials discussed herein will prove equally effective on all streams where such materials exist.”25

Preserved at the Museum

One fly can tell many stories. It knows the flora and fauna of various places, and is the result of art and craft. These five flies were produced by Art Flick’s hands and then passed (in order) to John Voelker, Bill Nault, Trout Unlimited, Mike Stefanac, the author, and now, finally, to the American Museum of Fly Fishing. Over the course of half a century, the museum’s five Flick flies not only preserve the work of an angling giant, but also describe a relationship, a period of history, expertise, beauty, and thoughtful care. No doubt many thousands of flies in the museum’s collection have similarly rich stories to tell.

Art Flick donated this Red Quill to the collection of the American Museum of Fly Fishing. Accession no. 1978.052.001. Photo by Sara Wilcox

The Red Quill

One of the ten flies given to John Voelker by Art Flick was the Red Quill (the male Hendrickson), the only fly pattern that Flick originated. That Red Quill is part of Mike Anderegg’s collection, but the museum has one previously donated by Art Flick.

According to Flick:

The only fly I can claim to have originated is the Red Quill. That one I do take credit for. And it was a very peculiar thing. The Hendrickson, which Roy Steenrod tied so well, was on the market at the time, it was a fairly well known pattern as dry flies go. But I found out that in the Hendrickson hatch there was always, at least on the Schoharie, another fly that came along at the same time. It always seemed to be a male, whereas the Hendricksons always seemed to be females. And we finally boiled it down that it was the male of the Hendricksons. But they’re different as night and day. In the first place, the female has a very tiny eye as is usually the case with the females, while the other just had a normal dark eye. The one I called the Red Quill had a large eye and it was definitely on the reddish side. Its body was more reddish and other than that it was the same fly. The body is a quill type and with trial and error I found out that the stripped quill of a Rhode Island Red rooster made a pretty good imitation of it and I used it right along.

—Quoted in Roger Keckeissen, Art Flick, Catskill Legend: A Remembrance of His Life and Times (Point Reyes Station, Calif.: Clark City Press, 2015), 66.

Endnotes

- Ernest Schwiebert, Trout (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1978), 563.

- Robert Traver, “A Flick of the Favorite Fly,” Trout Magic (West Bloomfield, Mich.: Northmont Publishing Company, 1992), 33.

- John D. Voelker to Arthur B. Flick, 23 March 1961, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Correspondence Series, Box 43, Folder 39, Central Upper Peninsula and Northern Michigan University Archives, Marquette, Michigan.

- Arthur B. Flick to John D. Voelker, 5 April 1961, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Correspondence Series, Box 43, Folder 39.

- John D. Voelker to Arthur B. Flick, 17 April 1961, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Correspondence Series, Box 43, Folder 39.

- Ibid.

- Arthur B. Flick to John D. Voelker, 24 April 1961, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Correspondence Series, Box 43, Folder 39.

- Ibid.

- Bill Nault, verification statement, accession no. 2016.018.006, American Museum of Fly Fishing, Manchester, Vermont.

- John D. Voelker to Arthur B. Flick, 4 May 1961, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Correspondence Series, Box 43, Folder 39.

- Robert Traver, “A Flick of the Favorite Fly,” Trout Magic, 31–47.

- John D. Voelker, “Fishing Notes,” 27–29 June 1962, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Personal Series, Box 6, Folder 27. Also, Robert Traver (with photographs by Robert W. Kelley), Anatomy of a Fisherman (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1964).

- John D. Voelker, “Fishing Notes,” 29 June–4 July 1962, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Personal Series, Box 6, Folder 27.

- John D. Voelker, “Fishing Notes,” 1 July 1962, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Personal Series, Box 6, Folder 27.

- John D. Voelker, “Fishing Notes,” 2 July 1962, MSS-39: John D. Voelker Papers, Personal Series, Box 6, Folder 27.

- Bill Nault, “A Day to Remember,” Michigan Out of Doors (March 1990), 66.

- Bill Nault, verification statement, accession no. 2016.018.006, 5, American Museum of Fly Fishing, Manchester, Vermont.

- Mike Anderegg, e-mail to author, 3 August 2016.

- Schwiebert, 175.

- Mike Stefanac, telephone conversation with author, 17 July 2016.

- Roger Keckeissen, Art Flick, Catskill Legend: A Remembrance of His Life and Times (Point Reyes Station, Calif.: Clark City Press, 2015), 63.

- Ibid.

- Dick Talleur, Talleur’s Dry-Fly Handbook (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1992), 38.

- Ibid.

- Art Flick, New Streamside Guide to Naturals and Their Imitations (New York: Crown Publishing, Inc., 1969), xix.

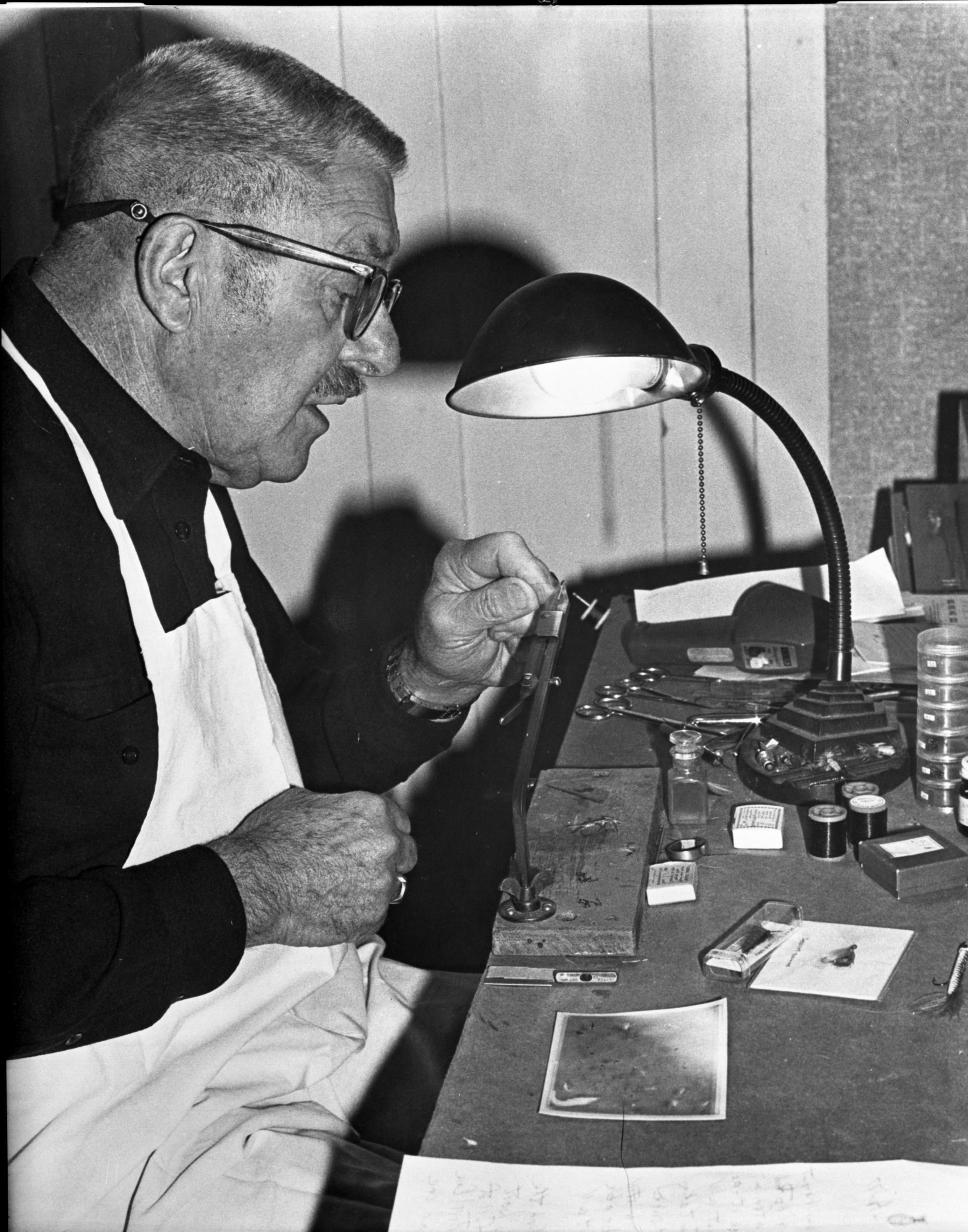

Art Flick at his fly-tying bench, West Kill, New York, circa 1950s. From the collection of William Flick and used with permission.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2017 (Vol. 43, No. 1) issue of the American Fly Fisher.